Wonders of the Seas: Coral Reefs

Discover the wonders of coral reefs, vibrant ecosystems teeming with marine life. Explore their biodiversity, threats, and conservation efforts.

Coral reefs, often called the “rainforests of the sea,” are among the most biodiverse and vibrant ecosystems on Earth. These underwater marvels, built by tiny animals called coral polyps, support an astonishing array of marine life and play a critical role in ocean health. From the sprawling Great Barrier Reef to the colorful reefs of the Indo-Pacific, coral reefs captivate adventurers and scientists alike with their kaleidoscopic beauty and ecological significance. However, these fragile ecosystems face growing threats from climate change, pollution, and human activity, making conservation efforts more urgent than ever. This article dives into the wonders of coral reefs, their biodiversity, their role in marine ecosystems, and the critical need to protect them for future generations.

The Ancient Architects: What Are Coral Reefs?

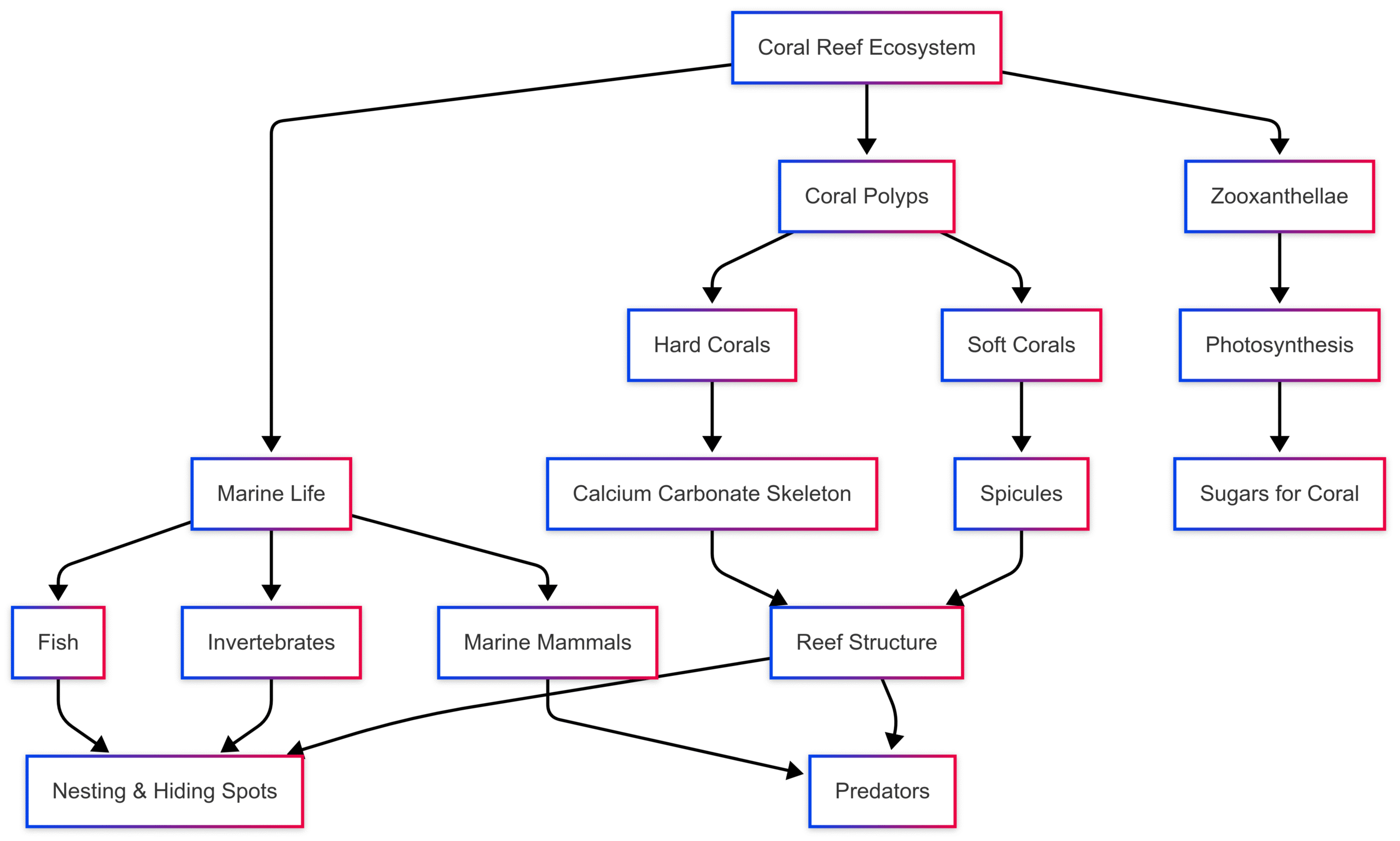

Coral reefs are complex, living structures formed by calcium carbonate secretions from tiny marine animals called coral polyps. These polyps, members of the cnidarian phylum alongside jellyfish and anemones, are soft-bodied creatures with a mouth surrounded by tentacles equipped with stinging cells called nematocytes. While jellyfish use these cells to capture prey, coral polyps pose little threat to humans but are deadly to small planktonic organisms like fish larvae and crustaceans.

Unlike solitary anemones, coral polyps live in colonies, sometimes numbering thousands within a single structure. These colonies, over centuries or millennia, build massive reef systems by depositing layers of calcium carbonate, forming limestone skeletons. Hard corals, also known as reef-building corals, create the rigid, boulder-like structures that form the backbone of reefs. For example, brain coral colonies can grow over 10 feet wide, while entire reef systems, like the Great Barrier Reef, stretch thousands of kilometers.

Soft corals, such as sea fans and sea whips, contribute to reef diversity with their flexible, plant-like forms. Instead of rigid skeletons, they produce tiny calcium carbonate spicules embedded within their tissues, allowing them to sway with ocean currents. Coralline algae, another key contributor, cement reefs together with thin layers of calcium carbonate, enhancing structural integrity.

Reefs are ancient, with origins dating back over 500 million years, predating terrestrial life. Some modern coral species are nearly identical to fossils from the dinosaur era, showcasing their resilience through eons of environmental change. Despite occupying less than 0.1% of the ocean floor, coral reefs host over 25% of marine species, making them biodiversity hotspots rivaling tropical rainforests.

The Great Barrier Reef: A Global Marvel

The Great Barrier Reef, located off Queensland, Australia, is the largest coral reef system on Earth, spanning over 2,300 kilometers (1,430 miles) and comprising more than 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands. Visible from space, it is the world’s largest structure built by living organisms, a testament to the power of coral polyps. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981, it supports an extraordinary diversity of life, including over 400 coral species, 1,500 fish species, 4,000 mollusk species, and six of the world’s seven sea turtle species.

The reef’s vibrant coral formations, from branching staghorn corals to massive brain corals, create a mesmerizing underwater landscape. It serves as a critical habitat for marine life, providing food, shelter, and breeding grounds for species like clownfish, manta rays, and humpback whales. Beyond its ecological role, the Great Barrier Reef holds cultural significance for Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander communities and generates over $3 billion annually from tourism.

However, the reef faces severe threats. Since 1985, it has lost over half its coral cover due to climate change, coral bleaching, and outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish. Conservation efforts, including marine protected areas and sustainable tourism practices, are vital to its survival.

Biodiversity Hotspots: The Coral Triangle and Beyond

While the Great Barrier Reef is iconic, the Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia—encompassing waters around Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea—is the most biologically diverse marine region on Earth. This area hosts an unparalleled variety of coral and marine species, with vibrant reefs teeming with colorful fish, sea turtles, and invertebrates. Other notable reef systems include the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef in the Caribbean and the Apo Reef in the Philippines, each showcasing unique biodiversity and coral formations.

Coral reefs support a staggering array of life. A single two-acre reef can host more fish species than the total number of bird species in North America. This diversity stems from the complex habitats reefs provide, offering nesting areas, hiding spots, and food sources for countless organisms. Larger predators, such as sharks and marine mammals, are drawn to reefs for prey, creating a dynamic food web.

| Reef System | Coral Species | Fish Species | Other Notable Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Barrier Reef | 400+ | 1,500+ | Sea turtles, dugongs, sharks |

| Coral Triangle | 600+ | 2,000+ | Manta rays, whale sharks |

| Mesoamerican Barrier Reef | 60+ | 500+ | Manatees, crocodiles |

| Apo Reef (Philippines) | 100+ | 400+ | Hawksbill turtles, reef sharks |

How Coral Reefs Function: A Symbiotic Marvel

Coral reefs thrive in nutrient-poor tropical waters, a paradox given their biodiversity. The key lies in the symbiotic relationship between coral polyps and zooxanthellae, microscopic algae living within their tissues. These algae, through photosynthesis, produce sugars that provide up to 90% of the coral’s energy needs. In return, corals supply zooxanthellae with carbon dioxide and nutrients from their waste. This mutualism allows corals to flourish in clear, low-nutrient waters, where plankton is scarce.

Zooxanthellae give corals their vibrant colors, ranging from green to brown, and restrict reef growth to shallow waters (less than 75 meters) where sunlight penetrates. Coral polyps supplement their diet by capturing plankton with their nematocyte-laden tentacles at night. This dual feeding strategy—photosynthesis by day, predation by night—makes corals highly efficient in nutrient-scarce environments.

Reef growth varies by species. Fast-growing staghorn corals can add up to 6 inches annually, while slower species, like brain corals, grow less than an inch per year. Over centuries, these incremental additions create massive structures, with some colonies exceeding 1,000 years in age.

Types of Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are classified into three main types, each with distinct characteristics:

- Fringing Reefs: Found close to shore, these reefs grow directly from the coastline, forming narrow bands of coral. They are common in the Caribbean and Indo-Pacific.

- Barrier Reefs: Located farther offshore, these reefs create a barrier between shallow coastal waters and the open ocean, protecting lagoons. The Great Barrier Reef is the most famous example.

- Atolls: Circular reefs surrounding a lagoon, often mistaken for islands, atolls form on submerged volcanic rims. They are prevalent in the Pacific, such as in the Maldives.

Ecological and Economic Importance

Coral reefs are ecological powerhouses, supporting marine biodiversity and stabilizing coastal ecosystems. They act as nurseries for fish, protect coastlines from erosion by reducing wave energy by up to 97%, and sustain mangrove forests and seagrass beds. Reefs also recycle nutrients, improving water quality and supporting a complex food web.

Economically, coral reefs are invaluable, with a global worth estimated at $6 trillion annually. They support fisheries that feed over 500 million people and drive tourism industries, particularly in regions like the Caribbean and Australia. Additionally, coral-derived compounds are used in medicines for cancer, arthritis, and heart disease, while their skeletal structures inspire advanced bone-grafting materials.

Threats to Coral Reefs

Despite their resilience, coral reefs face existential threats:

- Climate Change and Coral Bleaching: Rising ocean temperatures disrupt the coral-zooxanthellae symbiosis, causing corals to expel their algae and turn white—a process known as bleaching. Major bleaching events in 1998, 2002, 2016, 2017, and 2020 have decimated reefs, with the Great Barrier Reef losing 29% of its coral in 2016 alone.

- Ocean Acidification: Increased CO2 absorption makes seawater more acidic, hindering coral’s ability to build calcium carbonate skeletons.

- Pollution and Runoff: Agricultural runoff and urban pollution introduce sediments and nutrients that foster harmful algae growth, smothering corals.

- Overfishing and Invasive Species: Overfishing disrupts food webs, while invasive species like the crown-of-thorns starfish devour corals.

- Unsustainable Tourism: Physical damage from divers and boats harms delicate reef structures.

Scientists predict that by 2050, 75% of reef-building corals could face high to critical threat levels, with up to one-third at risk of extinction.

Conservation Efforts: A Global Imperative

Protecting coral reefs requires a multifaceted approach:

- Climate Change Mitigation: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is critical to curbing ocean warming and acidification.

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): Expanding MPAs, like those in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, limits human impact and fosters ecosystem recovery.

- Water Quality Management: Controlling agricultural and urban runoff improves water clarity and reduces harmful algae.

- Sustainable Tourism: Certified operators enforce responsible practices, such as using reef-safe sunscreen and limiting visitor numbers.

- Invasive Species Control: Programs targeting crown-of-thorns starfish help protect coral cover.

- Scientific Research: Ongoing monitoring and research inform adaptive management strategies, while initiatives like the Coral Reef Alliance’s “adaptive reefscapes” promote resilience.

- Community Engagement: Educating locals and visitors fosters stewardship and supports conservation policies.

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Climate Change Mitigation | Reduce greenhouse gas emissions to curb ocean warming and acidification. |

| Marine Protected Areas | Designate zones to limit fishing and tourism impacts. |

| Water Quality Management | Control runoff to reduce sediment and nutrient pollution. |

| Sustainable Tourism | Enforce reef-safe practices and certify eco-friendly operators. |

| Invasive Species Control | Target species like crown-of-thorns starfish to protect coral. |

| Scientific Research | Monitor reefs and develop adaptive strategies for resilience. |

Experiencing Coral Reefs: Responsible Exploration

Visiting coral reefs offers an unparalleled adventure. The Great Barrier Reef, accessible from Cairns or Port Douglas, is a prime destination for snorkeling, scuba diving, and boat tours. The dry season (June to October) provides optimal conditions with calm seas and clear visibility. Travelers should:

- Choose Certified Operators: Select tours accredited by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority to ensure eco-friendly practices.

- Practice Reef Etiquette: Avoid touching corals, use reef-safe sunscreen, and maintain a safe distance from marine life.

- Prepare for Safety: Take snorkeling or diving courses if new to these activities, and use motion sickness remedies for boat trips.

- Capture Memories Responsibly: Use underwater cameras to document marine life without disturbing the ecosystem.

Helicopter or seaplane tours offer stunning aerial views, while island resorts in the Whitsundays provide direct reef access. Comprehensive travel insurance is recommended for emergencies.

How the Public Can Help

Everyone can contribute to coral reef conservation:

- Support Sustainable Tourism: Choose eco-certified operators and accommodations.

- Reduce Carbon Footprint: Opt for renewable energy and low-emission transport.

- Participate in Clean-ups: Join beach clean-up events to reduce marine debris.

- Advocate for Policies: Support legislation promoting reef protection.

- Educate and Donate: Learn about reef challenges and support conservation organizations.

Conclusion

Coral reefs are living wonders, sustaining marine biodiversity and human livelihoods while showcasing nature’s architectural brilliance. From the Great Barrier Reef’s vast expanse to the Coral Triangle’s vibrant diversity, these ecosystems are critical to ocean health and global economies. Yet, they face unprecedented threats from climate change, pollution, and human activity. By embracing responsible tourism, supporting conservation initiatives, and advocating for global environmental action, we can ensure that these underwater marvels endure for future generations. Dive into the wonders of coral reefs, and let their beauty inspire a commitment to their preservation.

Happy Boating!

Share Wonders of the Seas: Coral Reefs with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Mangrove, the wonder of marine habitats until we meet in the next article.