What do red and white lights on a boat mean?

Learn the meaning of red and white lights on boats, their role in navigation, and how they ensure safety at sea. Understand COLREGS and deck status lights.

Navigating the waters, whether for recreational boating or professional maritime operations, demands a clear understanding of navigation lights and their significance. Among the most critical are the red and white lights on boats, which play a pivotal role in ensuring safety, preventing collisions, and facilitating smooth maritime operations. These lights, governed by international regulations, communicate a vessel’s position, direction, and status to others on the water, especially in low-visibility conditions like night, fog, or rain. This article delves into the meaning of red and white lights on boats, their application in civilian and military contexts, and the rules that govern their use. It also explores related boating terminology, the logic behind navigation light colors, and practical tips for safe navigation.

The Role of Navigation Lights in Boating

Navigation lights are essential for safe maritime travel, acting as visual signals that convey critical information about a vessel’s position, direction, and operational status. These lights are particularly vital during nighttime or in conditions of reduced visibility, such as fog, rain, or heavy cloud cover. By adhering to standardized lighting protocols, mariners can avoid collisions and navigate crowded or narrow waterways effectively.

The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS), established by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), provide a universal framework for navigation light usage. These rules apply to all vessels, from small recreational boats to massive commercial ships and even seaplanes. Understanding these regulations is crucial for anyone operating a vessel, as they dictate how boats should interact to avoid accidents.

Red and Green Sidelights: Port and Starboard Indicators

One of the fundamental components of a boat’s navigation lighting system is the use of red and green sidelights. These lights indicate the port (left) and starboard (right) sides of a vessel, respectively:

- Red Light: Positioned on the port side, the red light signals the left side of the boat. When another vessel sees your red light, it indicates that you are approaching from their starboard side, and they may need to yield the right-of-way, depending on the situation.

- Green Light: Located on the starboard side, the green light denotes the right side of the boat. Seeing a green light suggests that you are approaching from their port side, and you may need to give way.

These sidelights are typically visible from dead ahead to 112.5 degrees aft on either side of the vessel, ensuring a wide arc of visibility. For smaller boats (under 65 feet), a combined red and green light, such as the NaviLED PRO Bi-Color Navigation Light, may be mounted at the bow along the centerline. According to COLREGS, these lights must be visible from at least 1 nautical mile (NM) for smaller vessels and 2 NM for larger ones, with the mounting height increasing for larger boats to ensure visibility.

White Lights: Stern and Masthead Indicators

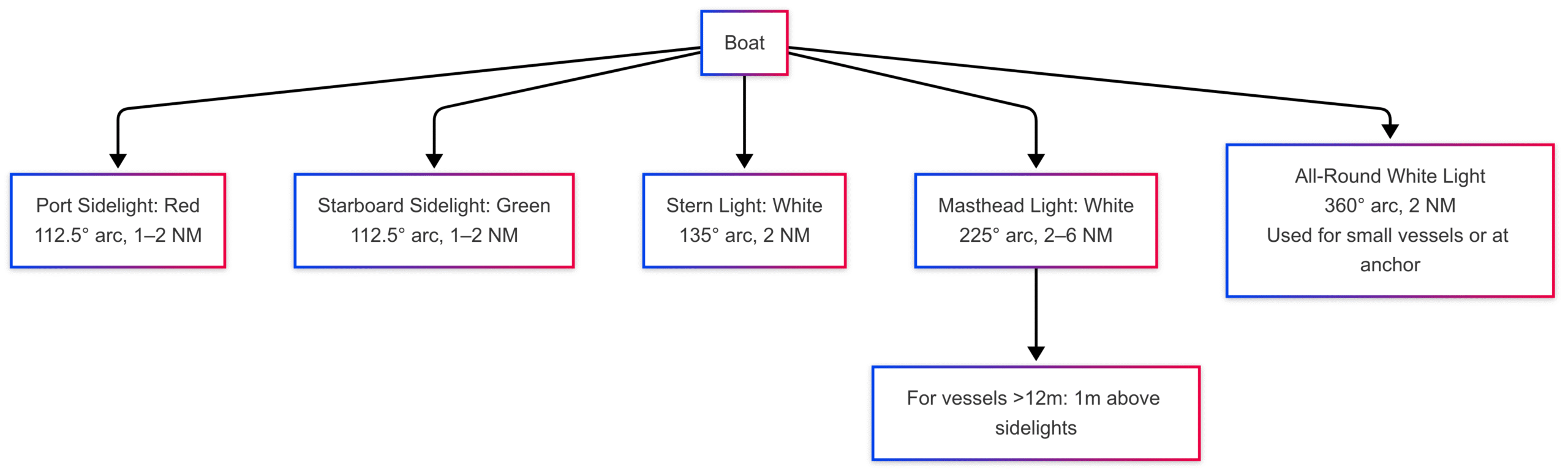

White lights on a boat serve multiple purposes, depending on their placement and configuration:

- Stern Light: A white light at the stern (rear) of the boat is visible over a 135-degree arc, covering the rear sector of the vessel. It indicates that the boat is moving away from an observer or is at anchor.

- Masthead Light: Found on power-driven vessels, the masthead light is a white light positioned higher than the sidelights (at least 1 meter higher for vessels over 12 meters). It shines forward over a 225-degree arc, indicating that the vessel is underway and powered.

- All-Round White Light: Used on smaller vessels (under 12 meters) or at anchor, this light is visible over 360 degrees. For example, a vessel at anchor displays an all-round white light, while a small boat moving slowly (under 7 knots and less than 7 meters) may use a single all-round white light instead of separate sidelights.

When both red and white lights are visible from another vessel, it typically means the boat is on your port side and moving toward you, requiring you to give way to avoid a collision.

The Logic Behind Red and Green Navigation Lights

A common question among boaters, as highlighted in online discussions, is why red and green lights are used instead of green-to-green passing, which might intuitively seem safer, given green’s association with “go” in traffic systems. The choice of red for port and green for starboard has historical and practical roots:

- Historical Origins: The use of red and green lights dates back to the 19th century, with the United Kingdom establishing these conventions in 1848. The British maritime influence, as noted in historical forums, standardized red for port and green for starboard, possibly drawing from the association of port wine with red, as humorously suggested by some mariners. These conventions were later adopted by the IMO to ensure global consistency.

- Practical Reasoning: Red, universally associated with caution or danger, signals the stand-on vessel in a crossing situation, alerting the give-way vessel to take action. Green, associated with safety, indicates the give-way vessel, which must yield to the vessel showing red. This system ensures that when two boats pass port-to-port (red-to-red), both operators see the “caution” signal, reinforcing the need for careful navigation. As one forum user noted, “Red to red = port to port = pass to the right,” aligning with the standard practice of passing oncoming traffic to the right, similar to driving conventions in many countries.

The “red to red” passing rule, governed by COLREGS Rule 14 (Head-On Situation), mandates that power-driven vessels meeting head-on should alter course to starboard to pass port-to-port. This minimizes confusion and ensures predictable movements, especially for large vessels with limited maneuverability. The mnemonic “Red, Right, Returning” further aids navigation by reminding boaters to keep red buoys on their starboard side when returning to shore, aligning with the port-to-starboard passing rule.

Navigation Light Specifications and Examples

Navigation lights must meet specific technical standards to comply with COLREGS:

| Light Type | Color | Arc of Visibility | Minimum Range | Mounting Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Port Sidelight | Red | 112.5° | 1–2 NM | Port side (left) |

| Starboard Sidelight | Green | 112.5° | 1–2 NM | Starboard side (right) |

| Stern Light | White | 135° | 2 NM | Stern (rear) |

| Masthead Light | White | 225° | 2–6 NM | Forward, above sidelights |

| All-Round Light | White | 360° | 2 NM | Centerline or mast |

For example, the Deck Mount LED Navigation Lamp Kit from Apex Lighting offers a robust solution for recreational boats, providing red and green sidelights that meet COLREGS requirements. Priced at approximately $50–$100, depending on the model, these LED lights are energy-efficient and durable, with a visibility range of up to 2 NM. For smaller vessels, the NaviLED PRO Bi-Color Navigation Light (around $80–$120) combines red and green lights in a single unit, ideal for boats under 65 feet.

Special Navigation Lights and Vessel Status

Beyond standard sidelights and white lights, certain vessels display unique light configurations to indicate their operational status:

- Vessels Not Under Command: These vessels, unable to maneuver due to mechanical failure, display two all-round red lights in a vertical line (or two red balls during the day). They have the highest priority in the right-of-way hierarchy.

- Vessels Restricted in Ability to Maneuver: Vessels engaged in activities like dredging or towing show three lights in a vertical line (red-white-red) or a ball-diamond-ball shape during the day. They take precedence over most other vessels, except those not under command.

- Vessels Constrained by Draft: Large ships restricted to deep channels display three all-round red lights in a line or a cylinder during the day, indicating they cannot deviate from their course.

- Fishing Vessels: These show a red-over-white light (or two triangles point-to-point) when fishing, or green-over-white when trawling, signaling their restricted maneuverability.

- Pilot Vessels: Identified by a white-over-red light, remembered by the rhyme “White over red, the pilot is out of bed.”

- Towing Vessels: Display two (for tows under 200 meters) or three (for tows over 200 meters) all-round white lights, with a yellow stern light instead of white.

These configurations ensure that other mariners can quickly assess a vessel’s status and take appropriate action, reducing the risk of collisions.

Diagram: Navigation Light Configurations

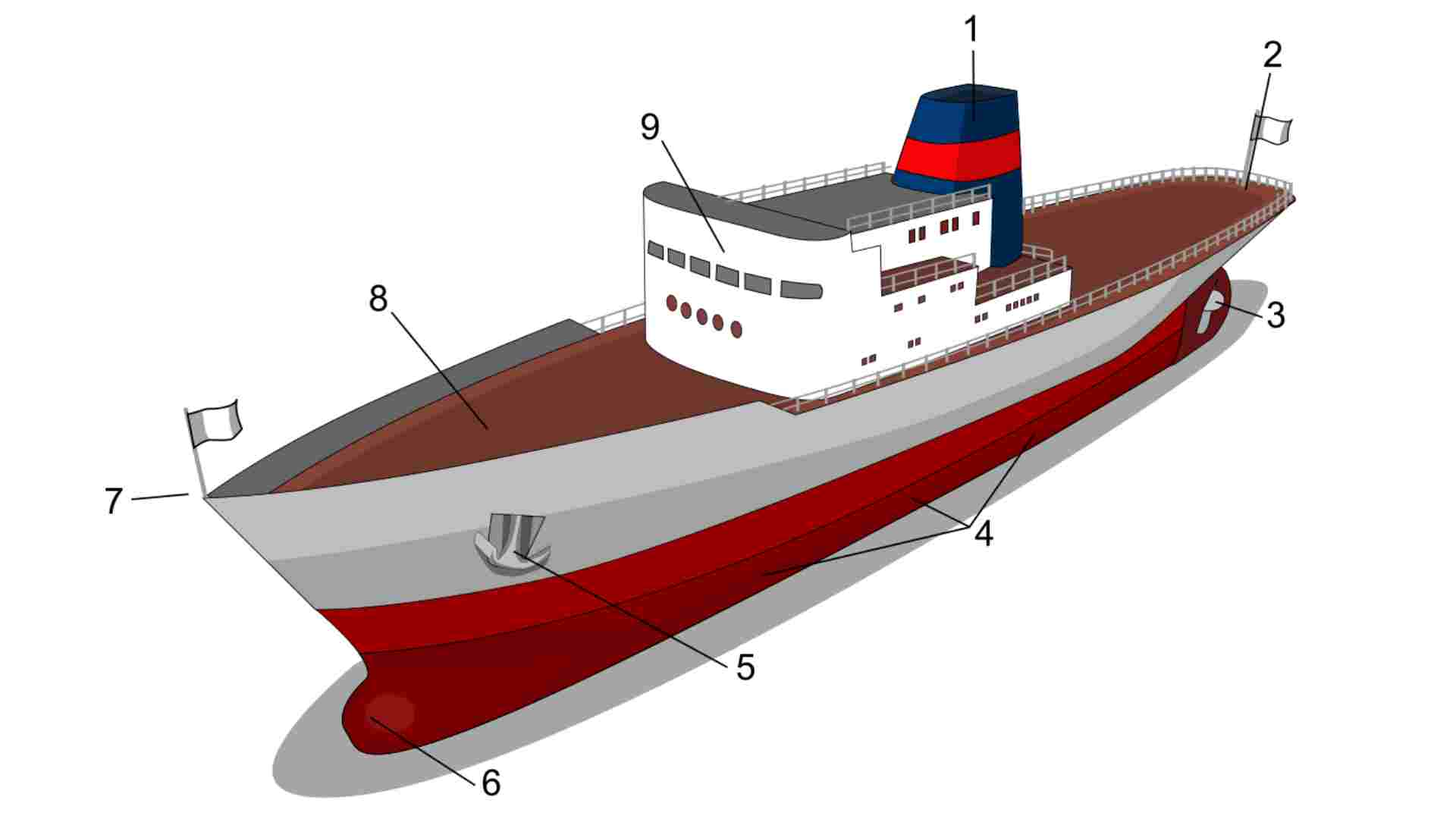

To illustrate the placement of navigation lights on a power-driven vessel, here is a diagram:

This diagram shows the typical arrangement of lights on a power-driven vessel, highlighting their arcs of visibility and placement.

Deck Status Lights in Military Operations

In military contexts, particularly on aircraft carriers, red and white lights take on a different role as part of the deck status light system. These lights communicate the operational status of the flight deck to pilots and crew, ensuring safe aircraft operations:

- Red Light: Indicates the deck is unsafe for takeoff or landing, often due to obstructions, ongoing operations, or hazards.

- Green Light: Signals that the deck is clear and safe for takeoff or landing.

- Amber Light: Denotes a fouled deck or one being prepared for aircraft handling, indicating caution.

These lights are controlled from the Primary Flight Control (Pri-Fly) center, allowing the air boss to manage deck operations efficiently. For example, on the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69), deck status lights streamline the coordination of F/A-18 Hornet launches and landings. Similarly, the HMS Queen Elizabeth (R08) uses these lights to manage F-35B Lightning II operations, ensuring safety during high-intensity missions.

The color-coded system is intuitive, leveraging the universal association of red with “stop” and green with “go.” This clarity is critical in high-stakes environments where verbal communication may be impractical due to noise or distance. The lights are visible from great distances, aiding pilots in assessing deck conditions well before approaching the carrier.

Boating Terminology: Understanding the Vessel

To fully grasp the context of navigation lights, it’s essential to understand key boating terms:

- Hull: The body of the boat, providing structural integrity.

- Gunwales: The upper edges of the hull, adding rigidity.

- Transom: The stern’s cross-section, where outboard motors are mounted.

- Cleats: Metal fittings for securing ropes during docking.

- Bow: The front of the boat.

- Stern: The rear of the boat.

- Port: The left side when facing the bow.

- Starboard: The right side when facing the bow.

- Beam: The widest point of the boat, affecting stability.

- Draft: The distance from the waterline to the keel, determining the minimum water depth needed.

- Freeboard: The distance from the waterline to the gunwale.

- Keel: The hull’s lowest point, providing stability and preventing sideways drift.

A handy mnemonic for remembering port is that it has the same number of letters as “left” (four), distinguishing it from starboard.

COLREGS: The Rules of the Road

The COLREGS provide a comprehensive framework for maritime navigation, ensuring consistency across global waters. Key rules relevant to navigation lights include:

- Rule 2 (Responsibility): All vessels must maintain a proper lookout using all available means (eyes, ears, radar, AIS) to assess collision risks.

- Rule 5 (Lookout): A proper lookout is mandatory at all times, as other rules depend on awareness of surrounding vessels.

- Rule 6 (Safe Speed): Vessels must operate at a speed that allows sufficient time to avoid collisions, considering visibility, traffic, and sea conditions.

- Rule 14 (Head-On Situation): Power-driven vessels meeting head-on must alter course to starboard to pass port-to-port (red-to-red).

- Rule 15 (Crossing Situation): The vessel seeing another on its starboard side (showing red) must give way, preferably by turning to starboard to pass astern.

- Rule 18 (Responsibilities Between Vessels): Establishes a hierarchy where vessels not under command have the highest priority, followed by those restricted in maneuverability, constrained by draft, fishing vessels, sailing vessels, power-driven vessels, and seaplanes.

In narrow channels, vessels should keep to the starboard side and pass port-to-port. Smaller boats must give way to larger vessels constrained by draft, such as ships in dredged channels, which may signal five short blasts to indicate “Get out of my way!” Overtaking vessels must give way, signaling intentions with two long and two short blasts to pass on the port side.

Challenges and Practical Tips for Night Navigation

Navigating at night poses unique challenges, as highlighted by mariners in online forums. Without radar or AIS, judging the distance and size of another vessel based on its lights can be difficult. A large ship far away may appear similar to a small boat nearby, complicating collision risk assessments. To address this:

- Use Reference Points: Line up another vessel with a fixed point on your boat (e.g., a stanchion). If the bearing remains constant, a collision risk exists, requiring action.

- Slow Down or Stop: In uncertain situations, reduce speed or stop to assess the other vessel’s intentions, as suggested by experienced boaters.

- Assume Ignorance: Many recreational boaters are unaware of COLREGS, so err on the side of caution, even if you have the right-of-way.

- Use Additional Tools: If equipped, leverage radar or AIS to supplement visual and auditory lookouts, enhancing situational awareness.

Regional Variations in Buoyage Systems

While navigation lights are standardized globally, buoyage systems vary. The International Association of Lighthouse Authorities (IALA) defines two systems:

- IALA Region A: Used in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Australia, where green buoys are kept to starboard when returning from the sea.

- IALA Region B: Used in North and South America, Japan, and parts of the Eastern Pacific, where red buoys are kept to starboard when returning (Red, Right, Returning).

These differences can confuse boaters traveling internationally, especially in low-visibility conditions. Always check local charts and regulations before navigating unfamiliar waters.

Conclusion

Red and white lights on boats are more than just visual markers; they are critical components of a global system designed to ensure safety and order on the water. Red lights signal the port side, guiding vessels to pass safely port-to-port, while white lights indicate a vessel’s stern, anchor status, or operational constraints. In military contexts, deck status lights on aircraft carriers use red and white to manage high-stakes flight operations. By understanding these lights, adhering to COLREGS, and mastering boating terminology, mariners can navigate confidently and safely. Whether you’re a recreational boater or preparing for an Ocean Yachtmaster course, knowledge of navigation lights is essential for mastering the art of seamanship.

For further learning, resources like the U.S. Coast Guard’s Navigation Rules (http://www.navcen.uscg.gov) and online courses from Sistership Training (https://sistershiptraining.com) offer valuable insights. Stay vigilant, keep a proper lookout, and let the red and white lights guide you safely across the seas.

Share What do red and white lights on a boat mean? with your friends and Leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Unlocking the Secrets: How to Identify a Tule Salmon? until we meet in the next article.