Ship Materials and Welding Techniques

Shipbuilding stands as one of the most demanding engineering fields, where the selection of materials and the precision of welding techniques determine the vessel’s ability to endure the relentless forces of the ocean. From massive cargo carriers to sleek naval ships, every structure relies on robust materials joined through advanced welding processes. This comprehensive guide delves into the core materials used in marine construction—steel, aluminum, and composites—and examines the welding methods that ensure structural integrity, corrosion resistance, and long-term performance in harsh saltwater environments.

Core Materials in Ship Construction

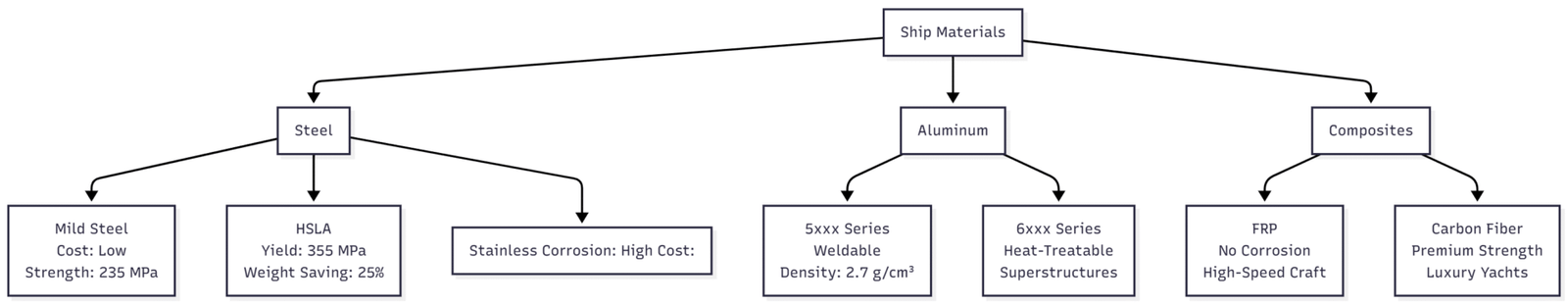

The foundation of any ship lies in its materials, chosen for strength, weight, durability, and resistance to marine corrosion. Steel dominates the industry, but aluminum and composites play critical roles in specific applications.

Steel: The Backbone of Shipbuilding

Steel remains the primary material for ship hulls, decks, and superstructures due to its exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and affordability. High-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels, such as AH36 and DH36 grades, are standardized by classification societies like the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) and Lloyd’s Register. These steels offer yield strengths of 355 MPa, making them ideal for load-bearing structures.

- Mild Steel: Used for general fabrication; cost-effective but requires protective coatings.

- High-Tensile Steel: Reduces overall weight by 20-30% compared to mild steel, improving fuel efficiency.

- Stainless Steel: Employed in piping and tanks for superior corrosion resistance.

Steel’s weldability is excellent with proper preheating (typically 100-150°C for thick plates) to prevent cracking. Post-weld heat treatment normalizes the heat-affected zone (HAZ), restoring ductility.

| Material | Yield Strength (MPa) | Typical Applications | Corrosion Resistance |

| Mild Steel | 235 | Secondary structures | Low (needs coating) |

| AH36 HSLA | 355 | Hull plating | Moderate |

| Stainless 316L | 170 | Piping, tanks | High |

Aluminum Alloys: Lightweight and Corrosion-Resistant

Aluminum’s density (2.7 g/cm³ vs. steel’s 7.8 g/cm³) makes it perfect for superstructures, reducing the ship’s center of gravity and enhancing stability. Series 5xxx (e.g., 5083, 5383) and 6xxx alloys dominate marine use due to their weldability and resistance to seawater corrosion.

- Advantages: 40-50% weight reduction; natural oxide layer prevents pitting.

- Challenges: Lower melting point (660°C) requires precise heat control during welding.

GMAW with argon shielding is standard, producing clean joints with minimal distortion.

Composite Materials: Emerging Alternatives

Fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP) combine glass or carbon fibers with epoxy resins. Used in high-speed craft and non-structural components, composites offer:

- Strength-to-Weight Ratio: Comparable to steel but 70% lighter.

- Corrosion Immunity: No rust or galvanic issues.

- Applications: Patrol boats, yacht hulls, radar masts.

Joining composites often involves adhesive bonding rather than welding, though hybrid steel-composite structures use mechanical fasteners.

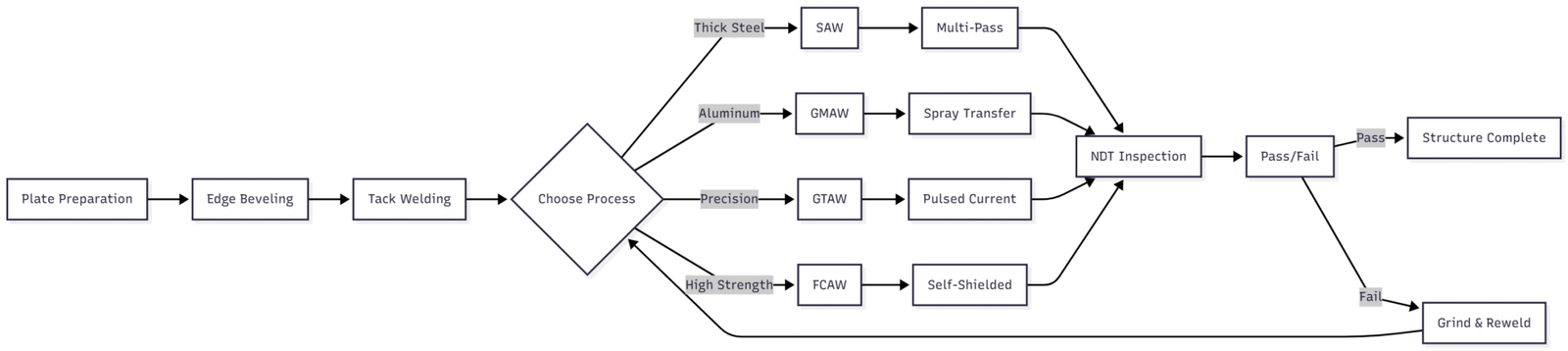

Welding Techniques in Marine Engineering

Welding joins 95% of a ship’s structural components, accounting for 3-5% of total weight (700-1150 tonnes on a 270m tanker). Precision is non-negotiable—excess heat weakens steel’s mechanical properties, while poor joints invite catastrophic failure.

Arc Welding Processes

Arc welding generates heat via an electric arc, melting base and filler metals to form a molten pool that solidifies into a joint.

Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW)

Also called “stick welding,” SMAW uses a consumable electrode coated in flux. The flux creates slag, shielding the weld from oxygen.

- Electrode Types: E6013 (general), E7018 (low-hydrogen for HSLA).

- Current: 90-400A DC.

- Positions: All-position capability.

- Applications: Repair work, thick plates (>6mm), outdoor shipyard conditions.

SMAW’s portability suits windy environments, but slag removal and electrode changes reduce productivity.

Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW/MIG)

GMAW feeds a continuous wire electrode through a gun, shielded by inert gas (argon/CO₂ mix).

- Wire Diameter: 0.8-1.6mm.

- Transfer Modes: Short-circuit (thin materials), spray (thick plates).

- Deposition Rate: 3-6 kg/h.

- Advantages: 80-95% efficiency; minimal cleanup.

Ideal for aluminum superstructures and automated lines.

Flux-Cored Arc Welding (FCAW)

Similar to GMAW but uses tubular wire filled with flux. Self-shielded variants need no external gas.

- Penetration: Deeper than GMAW.

- Wind Resistance: Excellent for shipyards.

- Applications: Hull construction, high-strength steels.

Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW/TIG)

Uses a non-consumable tungsten electrode with separate filler rod.

- Precision: ±0.1mm tolerance.

- Materials: Stainless, aluminum, titanium.

- Heat Input: Low (prevents distortion).

Critical for piping and fuel tanks.

Submerged Arc Welding (SAW)

The arc burns beneath a granular flux blanket, producing deep penetration.

- Wire: Single or twin (up to 2000A).

- Speed: 1-2 m/min.

- Thickness: >6mm.

- Automation: Fully robotic.

Dominates hull longitudinal seams.

| Process | Heat Input (kJ/mm) | Deposition (kg/h) | Best Thickness |

| SMAW | 1.5-3.0 | 3-Jan | 3-50mm |

| GMAW | 0.8-2.0 | 8-Mar | 1-25mm |

| FCAW | 1.2-2.5 | 10-Apr | 5-100mm |

| GTAW | 0.5-1.5 | 0.5-2 | 0.5-10mm |

| SAW | 2.0-4.0 | 15-May | >6mm |

Gas Welding (Oxy-Fuel)

Uses a flame (3500°C) from oxygen-acetylene mix. Limited to thin plates (<3mm) and repairs.

- Filler: Matching base metal.

- Distortion: High risk.

Rare in modern shipbuilding but useful for intricate pipework.

Resistance Welding

Applies pressure and current to fuse metals without filler.

- Spot Welding: Joins overlapping sheets (0.5-3mm).

- Seam Welding: Continuous joints for tanks.

- Speed: 60 spots/min.

Used for non-structural assemblies.

Advanced Techniques

Plasma Arc Welding (PAW)

Concentrates arc through a nozzle, reaching 28,000°C.

- Penetration: 20mm single pass.

- Distortion: Minimal.

For pressure vessels and thin materials.

Friction Stir Welding (FSW)

Solid-state process using a rotating pin to plasticize metals.

- Heat: <80% of melting point.

- Defects: Near-zero.

- Materials: Aluminum, dissimilar metals.

Gaining traction for side shell joints.

Laser Beam Welding

Uses focused light (CO₂ or Nd:YAG) for deep penetration.

- Speed: 5-10 m/min.

- Precision: ±0.05mm.

- Cost: High initial ($500,000+ systems).

Military applications for airtight seams.

Welding Procedure Specifications (WPS)

Every weld follows a WPS—a documented roadmap ensuring consistency.

Key Parameters:

- Base Metal: Grade, thickness.

- Filler: AWS classification (e.g., ER70S-6).

- Preheat: 100-200°C for HSLA.

- Voltage/Amperage: 22-30V, 150-350A.

- Travel Speed: 20-50 cm/min.

- Post-Heat: 600°C for stress relief.

WPS compliance is audited by ABS, DNV, or Lloyd’s.

Welder Qualifications and Training

Welders must hold certifications (e.g., AWS D1.1, ASME IX) renewed every 3 years.

Testing:

- 6G position pipe weld.

- Visual + RT/UT examination.

- Bend tests for ductility.

Mastery of SMAW, GMAW, FCAW, and GTAW required.

Quality Assurance and Inspection

Non-destructive testing (NDT) verifies weld integrity.

Visual Inspection (VT)

- Tools: Magnifiers, borescopes.

- Defects: Undercut, porosity, overlap.

Ultrasonic Testing (UT)

- Frequency: 2-5 MHz.

- Detects: Lack of fusion, cracks >0.5mm.

Radiographic Testing (RT)

- Source: Ir-192 gamma.

- Film: Reveals internal voids.

Magnetic Particle Testing (MT)

- For ferromagnetic materials.

- AC yoke detects surface cracks.

Dye Penetrant Testing (PT)

- For non-ferrous.

- Red dye + developer.

Acceptance criteria per AWS D1.1:

- No cracks.

- Porosity <2% of weld length.

- Undercut <0.5mm.

Challenges in Ship Welding

Distortion and Warping

Cause: Uneven heating/cooling.

Solution:

- Preheating.

- Balanced welding sequences.

- Clamping fixtures.

Cracking

Types:

- Hot (solidification).

- Cold (hydrogen-induced).

- Lamellar tearing.

Prevention:

- Low-hydrogen electrodes.

- Post-weld heat treatment (PWHT).

Corrosion at Welds

Issue: Galvanic action in HAZ.

Mitigation:

- Cathodic protection.

- Epoxy coatings (200-300μm DFT).

- Weld metal overmatching.

Harsh Environments

Wind disperses shielding gas; humidity causes porosity.

Countermeasures:

- FCAW self-shielded wire.

- Windbreaks.

- Automated welding robots.

Evolution of Ship Welding

Riveting dominated until the 1940s—labor-intensive, leak-prone. Liberty ships during WWII showcased welding’s superiority, reducing construction time by 60%. Modern automation (Bug-O systems, robotic arms) achieves 99% uptime.

Best Practices

- Material Prep: Clean surfaces (SSPC-SP10).

- Fit-Up: Gap <1.5mm, misalignment <10% thickness.

- Sequence: Back-step or block welding.

- Monitoring: Infrared cameras for heat control.

- Documentation: Digital WPS with QR codes.

Equipment Specifications

| Equipment | Model | Power | Price (USD) | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIG Welder | Lincoln Power Wave S350 | 350A | 8,500 | Pulsed modes, aluminum capable |

| TIG Welder | Miller Dynasty 400 | 400A | 12,000 | AC/DC, high-frequency start |

| SAW System | ESAB Aristo 1000 | 1000A | 45,000 | Twin-wire, flux recovery |

| Robotic Arm | ABB IRB 2600 | 6-axis | 75,000 | 20kg payload, 1.65m reach |

Future Trends

- Hybrid Laser-Arc: Combines precision and speed.

- AI Monitoring: Real-time defect prediction.

- Additive Manufacturing: 3D-printed weld fillers.

- Green Welding: Reduced emissions via inverter power sources.

Ship materials and welding techniques form the unbreakable bond that allows vessels to conquer the seas. From selecting AH36 steel to executing flawless SAW seams, every decision impacts safety, efficiency, and longevity. As automation and materials science advance, shipbuilding continues evolving—yet the fundamental principles of strength, precision, and quality remain eternal.

Frequently Asked Questions

Steel, particularly high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) grades like AH36 and DH36, is the most widely used material due to its excellent strength-to-weight ratio (yield strength of 355 MPa), affordability, and proven weldability. It forms over 90% of a typical ship’s structural weight, enabling hulls to withstand extreme loads while keeping construction costs manageable. Protective coatings and cathodic systems further enhance its resistance to marine corrosion.

Submerged Arc Welding (SAW) is the preferred method for thick plates (>6 mm). It delivers deep penetration (up to 4 kJ/mm heat input), high deposition rates (5–15 kg/h), and automation compatibility, making it ideal for long, straight hull seams. Twin-wire SAW systems can achieve welding speeds of 1–2 m/min with minimal defects, ensuring structural integrity in cargo and tanker vessels.

Aluminum welding requires lower heat input (0.8–2.0 kJ/mm) due to its lower melting point (660°C vs. steel’s 1,500°C) and higher thermal conductivity. Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW/MIG) with argon shielding and pulsed current is standard to prevent burn-through and distortion. Aluminum also forms a natural oxide layer, necessitating AC current for cleaning during GTAW/TIG to ensure clean, high-quality joints in superstructures.

NDT ensures weld integrity without damaging the structure, detecting defects like cracks, porosity, or lack of fusion that could lead to catastrophic failure at sea. Ultrasonic Testing (UT) is the most common method for major structures (hulls, bulkheads) due to its accuracy in locating internal flaws (>0.5 mm), real-time graphical results, and safety compared to radiographic testing. UT is mandated by classification societies like ABS and DNV.

Automation, via robotic arms (e.g., ABB IRB series) and mechanized carriages (e.g., Bug-O systems), performs repetitive welds like SAW and GMAW with 99% uptime. Benefits include 30–50% faster production, consistent quality (tolerances ±0.1 mm), reduced welder exposure to fumes, and lower rework rates. Automated systems are essential for modular shipbuilding, cutting assembly time by up to 60% compared to manual methods.

Entry-level MIG welders start at $5,000–$10,000, while automated SAW systems with robotic integration range from $40,000–$150,000, depending on power (350–1000A), wire-feed precision, and flux recovery features.

Conclusion

Ship materials and welding techniques form the unbreakable foundation of modern maritime engineering, directly determining a vessel’s strength, safety, and service life in the world’s harshest environments. Steel, particularly high-strength low-alloy grades like AH36, remains the dominant material due to its optimal balance of tensile strength (355 MPa), weldability, and cost-effectiveness, comprising over 90% of structural weight in most commercial ships. Aluminum alloys enable lightweight superstructures that enhance stability and fuel efficiency, while advanced composites are increasingly adopted in high-performance craft for corrosion immunity and weight reduction.

Welding, accounting for 3–5% of a ship’s total mass, has evolved from manual riveting to precision-driven processes like Submerged Arc Welding (SAW), Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), and Flux-Cored Arc Welding (FCAW), each tailored to specific thicknesses, materials, and environmental challenges. Automation—powered by robotic systems and AI-monitored controls—has revolutionized productivity, achieving deposition rates up to 15 kg/h with near-zero defect rates. Strict adherence to Welding Procedure Specifications (WPS), welder certifications (AWS D1.1, ASME IX), and rigorous non-destructive testing (especially ultrasonic and radiographic methods) ensures compliance with global standards set by ABS, DNV, and Lloyd’s Register.

As ship designs push toward larger, greener, and smarter vessels, emerging technologies such as hybrid laser-arc welding, friction stir welding, and digital twin simulation are minimizing distortion, improving joint integrity, and reducing environmental impact. The future of shipbuilding lies in seamlessly integrating advanced materials science with intelligent welding systems—delivering vessels that are not only structurally superior but also operationally efficient, environmentally responsible, and resilient against the unrelenting forces of the sea.

Happy Boating!

Share Ship Materials and Welding Techniques with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read 50 Questions and Answers Asked in Oral Exam for Marine Third Engineer Officers until we meet in the next article.