Marine Propulsion Systems

Marine propulsion systems encompass the mechanisms and technologies that generate thrust to propel watercraft through water, enabling vessels to navigate oceans, rivers, and coastal areas efficiently. At its core, marine propulsion operates on fundamental physics principles, primarily Newton’s third law of motion, where a force exerted on the water (or air) produces an equal and opposite reaction that moves the vessel forward.

These systems have evolved dramatically from rudimentary human-powered methods to sophisticated mechanical, electrical, and hybrid setups, driven by advancements in engineering, fuel efficiency, emission regulations, and operational demands. In modern shipping, propulsion accounts for the majority of a vessel’s energy consumption—often up to 80-90% in large cargo ships—making optimization critical for economic viability, environmental compliance, and performance.

The discipline of marine engineering focuses on designing, integrating, and maintaining these systems, balancing factors like power output, fuel consumption, reliability, maneuverability, and environmental impact.

While small recreational boats may still rely on paddles, sails, or simple outboard motors, commercial and military vessels predominantly use internal combustion engines, electric motors, turbines, or impellers in pump-jets. This article delves into the history, types, working principles, specifications, advantages, disadvantages, and emerging trends in marine propulsion, providing a comprehensive guide for understanding how ships achieve speeds from a few knots in icebreakers to over 30 knots in high-speed ferries.

Historical Evolution of Marine Propulsion

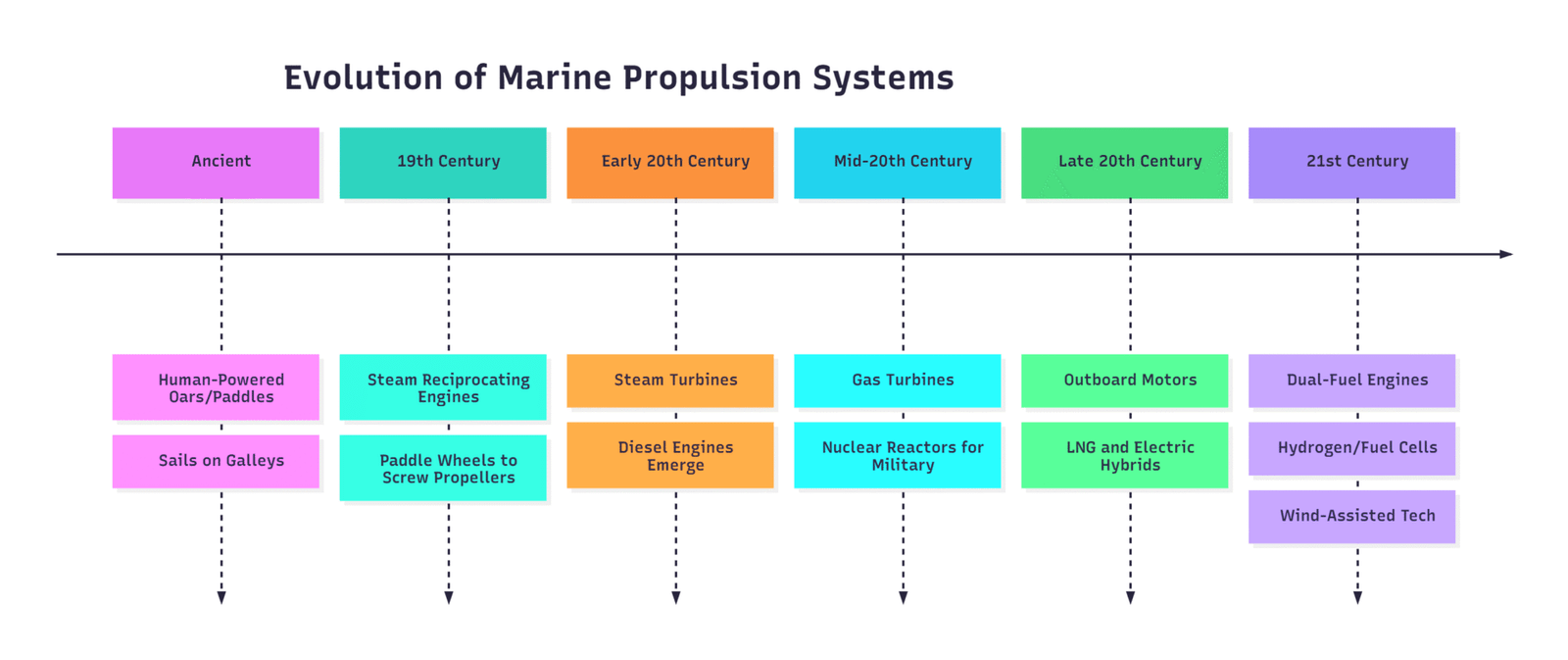

The journey of marine propulsion began with human ingenuity harnessing natural forces. Pre-mechanization relied on human-powered oars and paddles, dating back to 5000-4500 BCE, as evidenced by archaeological finds of ancient rowed vessels. Rowed galleys, often augmented with sails, dominated early seafaring and naval warfare, with iconic examples like Greek triremes in the Peloponnesian War and Roman ships at the Battle of Actium. These vessels used coordinated rowing to achieve maneuverability and speed, with galleys featuring multiple banks of oars for enhanced thrust.

Sails emerged as the next leap, utilizing wind energy via masts, stays, and rope-controlled lines. Merchant ships favored sails for long-distance trade, especially on wind-assured routes like the South American nitrate trade into the 20th century. Materials evolved from natural fibers to durable Dacron and modern laminated sails, reducing weaknesses in weaving. Even today, sails support recreation, racing, and fuel-saving innovations like rotor sails, turbo sails, wing sails, and kite systems on larger vessels.

Mechanization arrived in the early 19th century with the marine steam engine, pioneered by Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat (Clermont) in 1807 and Europe’s Comet in 1812. Steam reciprocating engines, fueled initially by wood then coal or oil, used paddle wheels before transitioning to screw propellers for efficiency. Multiple-expansion (compound) engines improved performance by reusing steam across cylinders. The steam turbine, invented by Sir Charles Parsons and demonstrated in the Turbinia in 1897, revolutionized high-speed liners with superior power-to-weight ratios.

The 20th century saw steam’s decline due to rising fuel costs, replaced by diesel engines—two-stroke or four-stroke—and gas turbines for speed. Outboard motors democratized small-boat propulsion. Nuclear reactors appeared in the 1950s for warships and icebreakers, producing steam without combustion, though commercial trials like NS Savannah failed due to high costs and design flaws. Recent decades highlight LNG-fueled engines for low emissions, Stirling engines for silent submarine operation, and electric battery systems for efficiency.

This timeline illustrates the progression, with each era building on prior efficiencies while addressing limitations like fuel availability and emissions.

Core Principles of Propulsion

All marine propulsion systems convert energy into thrust. Mechanical systems dominate, using engines to drive propellers or impellers. Thrust generation follows: Power → Shaft → Propeller/Impeller → Water Displacement → Forward Motion. Efficiency is measured by propulsive coefficient (typically 0.5-0.7), influenced by hull design, propeller efficiency (up to 80% in optimal fixed-pitch designs), and transmission losses.

Key metrics include:

- Specific Fuel Consumption (SFC): Grams of fuel per kWh (e.g., diesel: 180-200 g/kWh).

- Power Density: kW per ton (gas turbines excel here).

- Thrust-to-Weight Ratio: Critical for high-speed vessels.

| Metric | Diesel Engine | Gas Turbine | Electric Motor | Waterjet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFC (g/kWh) | 180-220 | 250-300 | N/A (depends on source) | N/A |

| Power Density (kW/ton) | 50-100 | 500-1000 | 200-500 | 300-600 |

| Efficiency (%) | 40-50 | 30-40 | 90-95 | 70-85 |

| Typical Speed (knots) | 15-25 | 25-40 | 10-30 | 30-50 |

Major Types of Marine Propulsion Systems

Diesel Engines

Diesel engines are the backbone of global shipping, powering over 90% of cargo vessels due to reliability, efficiency, and longevity (up to 30 years). They operate on compression ignition: air is compressed (ratio 14:1-20:1), fuel injected, ignites, expands, drives pistons, turns crankshaft, and propels via shaft.

- Two-Stroke vs. Four-Stroke: Two-stroke (common in large ships) completes cycle in one crankshaft revolution, using ports for intake/exhaust; ideal for slow-speed (80-120 rpm), high-power (up to 100,000 kW in MAN B&W or Wärtsilä engines). Four-stroke (medium/high-speed) uses valves, suits smaller vessels (300-1000+ rpm).

- Classification: Slow-speed (<300 rpm, crosshead design), medium-speed (300-1000 rpm, trunk piston), high-speed (>1000 rpm).

- Specifications: Example – Wärtsilä RT-flex96C (world’s largest): 14 cylinders, 108,920 kW, bore 960 mm, stroke 2500 mm, weight 2300 tons, SFC 169 g/kWh. Price: $50-100 million installed.

- Advantages: Fuel-efficient (HFO/MDO), direct-drive possible, redundant installations.

- Disadvantages: Emissions (SOx, NOx), vibration, maintenance-intensive.

- Applications: Cargo ships, tankers, bulk carriers. Direct coupling or gearbox for propellers.

In operation, slow-speed diesels connect directly to fixed-pitch propellers (diameter 9-10m, 4-6 blades, stainless steel/bronze, weight 100+ tons). Medium-speed use controllable-pitch propellers (CPP) for variable thrust without rpm changes.

Gas Turbines

Gas turbines suit high-speed needs, compressing air, mixing with fuel, igniting, expanding through blades to drive shaft. Lightweight (1/5th diesel weight) and compact.

- Working: Brayton cycle – Compressor (pressure ratio 20:1+), combustor, turbine.

- Specifications: GE LM2500: 25-35 MW, weight 20 tons, SFC 230 g/kWh, price $20-40 million.

- Advantages: High power (up to 50 MW/unit), quick start (minutes), low vibration.

- Disadvantages: High fuel use at low power, expensive fuel (MGO), heat-sensitive.

- Applications: Naval frigates, ferries, yachts (e.g., Alamshar: Pratt & Whitney ST40M, 70 knots, 50m length).

- Hybrids: CODAG/CODOG combine with diesel for cruise/sprint.

Steam Turbines

Once dominant, now niche. Steam from boilers drives blades; direct or turbo-electric.

- Types: Reciprocating (obsolete), impulse/reaction turbines.

- Specifications: MAN steam turbines for LNG carriers: 20-40 MW, efficiency 35-40%.

- Advantages: Smooth, high power.

- Disadvantages: Low efficiency at part-load, large boilers.

- Applications: LNG carriers (boil-off gas), nuclear vessels.

Nuclear variant: Reactor heats water to steam. Example – Arktika-class icebreaker: 55 MW, unlimited range. Commercial rare due to $1B+ costs.

Electric Motors and Diesel-Electric

Electric propulsion uses generators (diesel-driven) to power motors turning propellers/pods.

- Principle: AC/DC motors, variable frequency drives for speed control.

- Pod Propulsion: Azipods (ABB): 360° rotation, 5-20 MW, efficiency 95%, price $10-30 million/unit.

- Specifications: Siemens electric motors: 1-50 MW, torque 100-5000 kNm.

- Advantages: Quiet, maneuverable, efficient (no gearbox losses), hybrid potential.

- Disadvantages: Higher initial cost, battery limits.

- Applications: Cruise ships (Queen Mary 2), submarines, ferries. Battery-electric: 2400 kWh packs for 40nm range (e.g., Chinese coal carrier).

Hybrid examples: CODLAG (diesel cruise, gas sprint), IEP (full electric distribution).

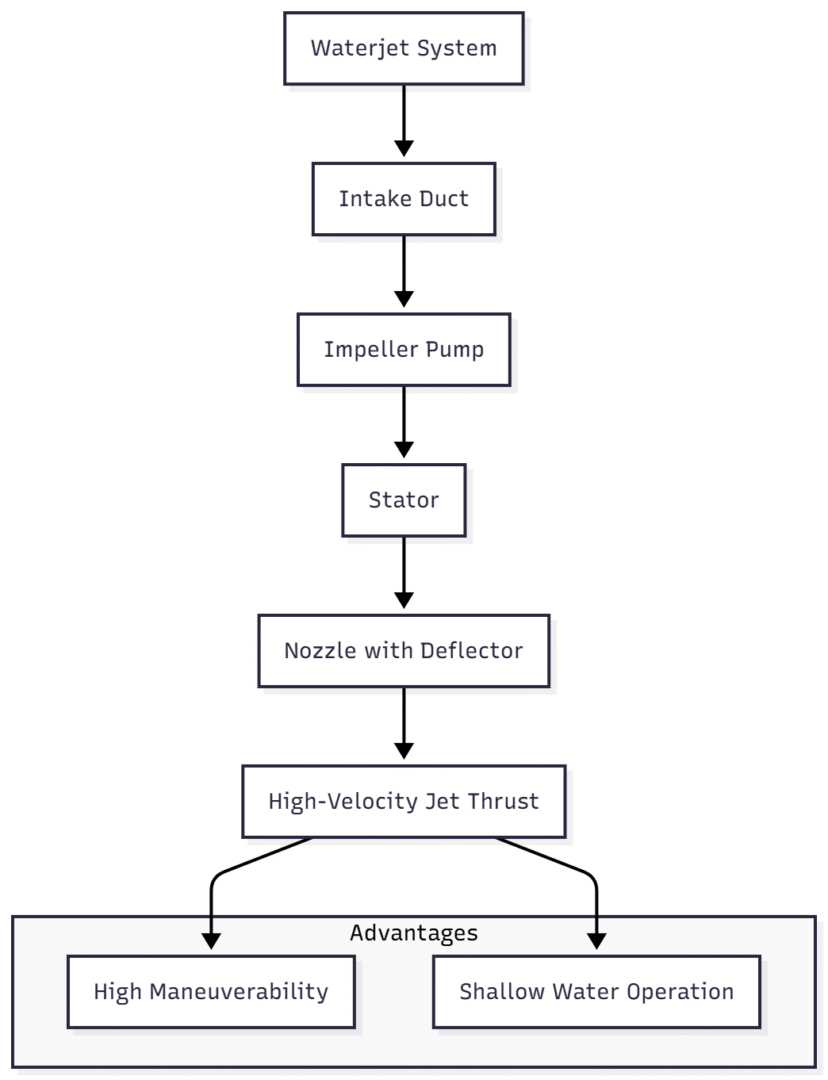

Waterjets

Impeller pumps water through nozzle for jet thrust.

- Working: Intake → Pump (axial/mixed-flow) → Nozzle (vectoring for steer).

- Specifications: HamiltonJet HJX: 500-3000 kW, speed 50+ knots, price $500k-5M.

- Advantages: High speed, shallow draft, no appendage drag.

- Disadvantages: Lower efficiency at low speeds, cavitation risk.

- Applications: Patrol boats, jetskis, ferries.

Alternative and Emerging Systems

LNG and Dual-Fuel Engines

LNG reduces SOx 99%, NOx 90%. Dual-fuel: Switch HFO/LNG.

- Specs: MAN ME-GI: 10-80 MW, methane slip <1%, price premium 20-30% over diesel.

- Advantages: Cost savings ($1-2M/year/vessel), compliance with IMO tiers.

- Applications: LNG carriers, cruises. BW LPG retrofits VLGCs.

LPG Engines

Similar to LNG, 97% SOx reduction.

- Specs: Retrofit kits $5-10M, efficiency +5%.

- Applications: Gas carriers.

Stirling Engines

Closed-cycle, external combustion; quiet.

- Specs: Kockums: 75 kW/sub, efficiency 30%.

- Applications: Submarines (Gotland-class).

Hydrogen and Fuel Cells

Electrochemical: H2 + O2 → Electricity + Water.

- Specs: PEM fuel cells: 100-5000 kW, efficiency 50-60%, H2 storage 700 bar.

- Advantages: Zero emissions.

- Disadvantages: Infrastructure, flammability.

- Applications: Prototypes (Maersk targets 2050 carbon-free).

Solar and Biodiesel

Solar: Panels + batteries, supplementary.

- Specs: 1-10 MW arrays, $1-5M.

Biodiesel: Blends (B20-B100), near-carbon-neutral.

Wind-Assisted

Flettner rotors, kites: 5-20% fuel savings.

Factors Influencing Choice

- Vessel Type: Cargo – diesel; Navy – gas/nuclear; Ferry – electric/hybrid.

- Regulations: IMO 2020 sulfur cap, EEDI for efficiency.

- Costs: Diesel cheapest upfront; LNG saves long-term.

- Performance: Propeller design (CPP vs. fixed), number (twin for redundancy).

| System | Initial Cost (per MW) | Operating Cost | Emissions | Lifespan (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | $500-1000 | Low | High | 25-30 |

| Gas Turbine | $1000-2000 | High | Medium | 20-25 |

| Electric | $1500-3000 | Medium | Low | 20-30 |

| LNG Dual-Fuel | $800-1500 | Low | Very Low | 25-30 |

| Nuclear | $5000+ | Very Low | Zero | 30+ |

Transmission and Propulsion Components

Power transmits via shafts, gearboxes, clutches. Propellers: Fixed-pitch (efficient, reverse via engine), CPP (variable, no reverse needed). Other: Paddle wheels (shallow rivers), Voith-Schneider (360° thrust, tugs), pump-jets (torpedoes).

Future Outlook

Decarbonization drives innovation: Ammonia, methanol, synthetic fuels. Hybrid/electric dominate newbuilds; nuclear revival for zero-emission deep-sea. Efficiency gains via AI optimization, contra-rotating pods.

Marine propulsion systems define maritime capability, from historical galleys to future atomic ships. Diesel remains king, but sustainability pushes LNG, electric, and alternatives. Selecting the right system optimizes speed, cost, and ecology, ensuring shipping’s role in global trade.

Frequently Asked Questions

A marine propulsion system generates thrust to move watercraft by converting energy (from fuel, electricity, or wind) into mechanical force, typically via propellers, waterjets, or pods, following Newton’s third law of motion.

Slow-speed two-stroke diesel engines directly coupled to fixed-pitch propellers are the most common, offering high efficiency (up to 50%), low SFC (169–180 g/kWh), and reliability for vessels like tankers and bulk carriers.

LNG reduces SOx by 99%, NOx by 90%, and fuel costs by $1–2 million annually per vessel. It enables seamless switching between LNG and diesel/HFO, ensuring compliance with IMO emissions rules.

Pure electric uses batteries or shore power; diesel-electric uses diesel generators to produce electricity for motors. Both offer 90–95% motor efficiency and superior maneuverability via podded thrusters (e.g., Azipods).

Hydrogen fuel cells (zero emissions), wind-assisted systems (5–20% fuel savings), biodiesel (near carbon-neutral), and advanced nuclear reactors enable long-range, zero-carbon operation for future deep-sea shipping.

Conclusion

Marine propulsion systems power global trade, defense, and exploration. Diesel engines dominate commercial shipping for efficiency and reliability, but LNG dual-fuel, electric/hybrid, and waterjet systems are rising to meet emissions and performance demands. Emerging technologies—nuclear, hydrogen, wind-assisted, and biofuels—promise zero-emission, high-efficiency futures. With propulsion consuming 80–90% of onboard energy, innovation in efficiency and sustainability is critical. The optimal system balances power, cost, and environmental impact, driving shipping toward a cleaner, smarter tomorrow.

Happy Boating!

Share Marine Propulsion Systems with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Ship Design and Construction until we meet in the next article.