Marine Engineering

Marine engineering stands as a cornerstone of global maritime operations, encompassing the intricate design, development, construction, operation, maintenance, and repair of mechanical, electrical, hydraulic, and electronic systems in boats, ships, submarines, offshore platforms, and other ocean-based structures.

This multidisciplinary field integrates principles from mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, electronic engineering, computer science, and ocean engineering to ensure vessels and marine infrastructure function efficiently, safely, and sustainably in harsh oceanic environments. Marine engineers play pivotal roles in propulsion, power generation, stability, environmental compliance, and emerging technologies, supporting everything from commercial shipping to military applications and renewable energy projects.

The profession demands a blend of theoretical knowledge and practical skills, addressing challenges like corrosion, hydrodynamic forces, cavitation, and pollution control. With over 80% of global trade by volume transported via sea on approximately 50,000 vessels, marine engineering is indispensable to the world economy.

This article delves into the core aspects of the field, including key systems, historical evolution, educational pathways, career progression, salaries, related disciplines, specific challenges, applications, and future prospects.

Defining Marine Engineering and Its Scope

At its essence, marine engineering focuses on the engineering of watercraft propulsion and ocean systems. It covers power and propulsion plants, machinery, piping, automation, control systems, and coastal/offshore structures. Unlike naval architecture, which prioritizes overall vessel design and hydrodynamics, marine engineering ensures onboard systems operate reliably. Marine engineers handle propulsion mechanics, electricity generation, lubrication, fuel systems, water distillation, lighting, air conditioning, and hydraulic controls.

The scope extends beyond ships to submarines, dynamic positioning vessels, offshore oil rigs, wind farms, wave energy converters, and port infrastructure. Engineers ensure seaworthiness under extreme conditions, including wave impacts, saltwater exposure, and remote operations. Compliance with international regulations like MARPOL for pollution and IMO standards for safety is integral.

Key expertise areas include:

- Propulsion Systems: Engines, propellers, shafts, and thrusters generating thrust.

- Electrical Systems: Power generation, distribution, lighting, navigation, and communication.

- HVAC Systems: Temperature, ventilation, and air quality control for crew and cargo.

- Hydraulic Systems: Rudder, bow thrusters, winches, and cargo handling.

- Structural Integration: Hull maintenance, stress analysis, and integrity checks.

- Safety Systems: Fire suppression, lifeboats, emergency lighting, and evacuation protocols.

Marine engineers collaborate with naval architects, oceanographers, and specialists to meet regulatory requirements and operational demands across diverse marine environments.

Historical Evolution of Marine Engineering

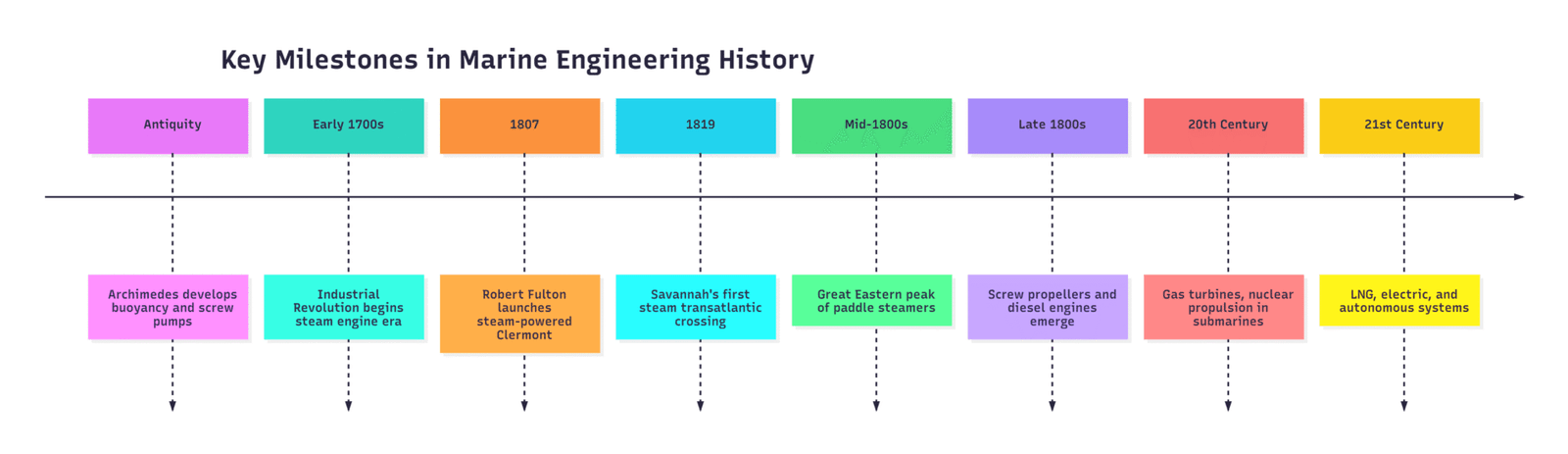

Marine engineering traces its roots to antiquity, with Archimedes credited as the first practitioner for innovations like the screw pump and buoyancy principles. Modern advancements began during the Industrial Revolution in the early 1700s.

A pivotal milestone occurred in 1807 when Robert Fulton integrated a steam engine into a vessel, powering a wooden paddle wheel on the Clermont. This marine steam engine marked the profession’s birth. By 1819, the Savannah completed the first transatlantic steam-assisted voyage. The mid-19th century saw peak paddle steamer development, culminating in the Great Eastern—a 700-foot, 22,000-ton behemoth rivaling modern cargo ships.

Paddle wheels gave way to screw propellers, diesel engines, gas turbines, and nuclear propulsion in submarines. Today, innovations include LNG-fueled engines, electric propulsion, and autonomous systems, driven by efficiency and emissions reduction needs.

Core Systems in Marine Engineering

Marine vessels rely on interconnected systems engineered for reliability.

Propulsion Systems

Propulsion generates forward motion. Diesel engines dominate commercial shipping, offering 20-50 MW output. Gas turbines provide high speed for naval vessels (up to 40+ knots). Nuclear reactors power submarines indefinitely. Propellers, azimuth thrusters, and waterjets optimize efficiency.

Specifications example: MAN B&W two-stroke diesel engines—bore 600-950 mm, stroke 2,000-3,500 mm, power 5,000-80,000 kW, efficiency ~50%.

Electrical Systems

Generators (diesel/alternators) produce 440-6,600V AC. Switchboards distribute power to motors, lights, and electronics. Battery banks support emergencies.

HVAC and Auxiliary Systems

HVAC maintains 20-25°C internals. Desalination plants produce 10-500 tons/day fresh water via reverse osmosis.

Automation and Control

PLC/SCADA systems monitor parameters. Dynamic positioning (DP) Class 2/3 vessels maintain position via GPS/thrusters accuracy <1m.

| System | Key Components | Typical Specifications | Maintenance Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propulsion | Diesel Engine, Propeller | Power: 10-50 MW; RPM: 100-500 | Overhaul every 20,000 hours |

| Electrical | Alternators, Switchboards | Voltage: 440V-11kV; Capacity: 1-10 MVA | Inspections every 1,000 hours |

| HVAC | Compressors, Ducts | Capacity: 100-5,000 kW cooling | Filter replacement monthly |

| Hydraulics | Pumps, Actuators | Pressure: 200-300 bar | Fluid change every 2 years |

Duties and Responsibilities of Marine Engineers

Marine engineers run the engine room—the beating heart of every ship. They keep propulsion, power, and life-support systems alive 24/7 in extreme conditions. Their work is technical, urgent, and non-stop. Below is a clear details of what they must do, day in, day out.

1. Daily System Monitoring & Logging

Check every critical parameter twice per watch (usually 4-hour shifts).

Key Checks:

- Main engine: oil pressure (4–6 bar), coolant temp (75–85°C), RPM.

- Generators: voltage (440V ±5%), load balance (<10% difference).

- Bilge levels, fuel tanks, lube oil sumps.

Action: Log all values in the Engine Log Book (legal document).

2. Planned Maintenance System (PMS)

Follow a digital or paper schedule to prevent breakdowns.

Examples:

| Equipment | Task | Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Fuel Injectors | Clean & test | 4,000 hours |

| Sea Water Pumps | Impeller replace | 8,000 hours |

| Air Compressors | Valve overhaul | 12,000 hours |

| Turbocharger | Wash | Weekly |

Tool: AMOS or TSM software — no task skipped.

3. Emergency Response & Troubleshooting

When the alarm sounds, they act in seconds.

Top 5 Emergencies & Immediate Actions:

| Alarm | Cause | First 60 Seconds |

|---|---|---|

| High Exhaust Temp | Fuel rack stuck | Reduce load → check pyrometer |

| Lube Oil Low Pressure | Pump failure | Start standby pump → isolate |

| Blackout | Generator trip | Start emergency generator (≤45 sec) |

| Flooding | Pipe burst | Close valve → start bilge pump |

| Fire in ER | Fuel leak | Activate CO₂ → evacuate |

4. Fuel Bunkering Operations

Take 1,000–5,000 tons of fuel safely.

Step-by-Step:

- Pre-bunker checklist (SOPEP, hoses, drip trays).

- Sound tanks → calculate exact volume (using tank tables).

- Sample fuel → test density, water, sulfur (<0.5% global).

- Pump at <200 m³/h → monitor for overflow.

- Sign Bunker Delivery Note (BDN) — legal proof.

5. Fuel Efficiency & Emissions Control

Goal is to burn <195 g/kWh (IMO target).

Actions:

- Trim optimization (software like NAPAs).

- Clean hull/propeller → save 5–10% fuel.

- Run scrubber in ECA zones (SOx <0.1%).

- Slow steaming (reduce speed 10% → save 25% fuel).

6. Crew Training & Drills

Monthly drills (IMO mandatory):

- Fire in engine room

- Man overboard

- Oil spill response

- Enclosed space entry

Marine Engineer Role:

- Demonstrate fire pump start in <30 sec.

- Train oiler on valve line-up.

- Sign drill log.

7. Regulatory Compliance & Reporting

Must submit:

- Oil Record Book (every transfer).

- IAPP/IEEC certificates (emissions).

- BWM Plan (ballast water).

Daily Routine (4-on/4-off Watch)

| Time | Task |

|---|---|

| 07:55 | Take over watch → read last log |

| 08:00–10:00 | Round of machinery spaces |

| 10:00 | Morning meeting with Chief |

| 12:00 | Lunch |

| 12:30–15:00 | Maintenance (PMS tasks) |

| 15:00 | Fuel/oil samples to lab |

| 16:00 | Hand over watch |

Educational Pathways and Training

Entry requires a bachelor’s degree: B.Eng./B.S. in Marine Engineering, Technology, or Systems. Curricula cover:

- Mathematics (calculus, differential equations).

- Fluid mechanics, thermodynamics.

- Geomechanics, control theory.

- Specialized: Hydromechanics, structural analysis.

Graduate degrees (M.Eng./M.S.) for licensure or research. Lateral entry from mechanical/electrical engineering possible with conversion courses.

Practical training via cadetships or apprenticeships. Institutions: California Maritime Academy, MIT, Indian Maritime University.

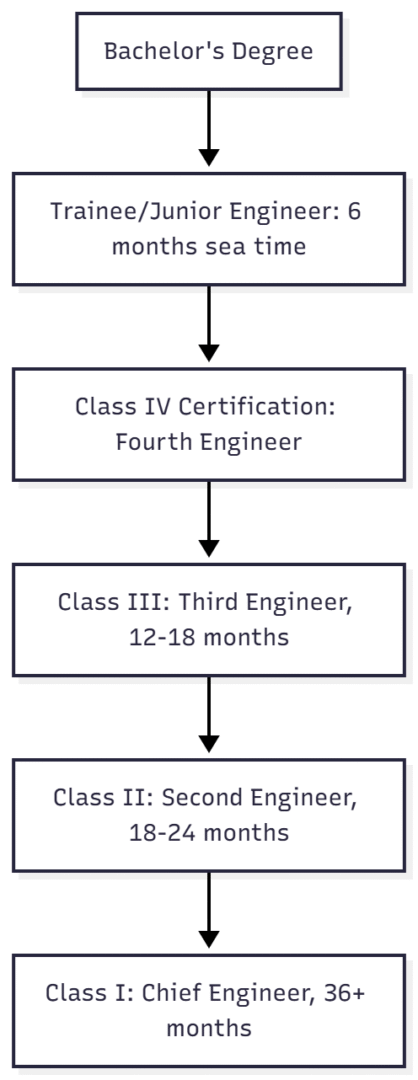

Certification progression:

Professional bodies: IMarEST, SNAME, RINA provide accreditation and CPD.

Career Progression and Opportunities

Start as junior engineer, advance to chief engineer. Promotion depends on sea time, exams, and company policy.

Work settings:

- Merchant Navy: Tankers, containers, passengers.

- Offshore: Rigs, wind farms.

- Shipyards: Construction/repairs.

- Military: Navy engineering corps.

- Design offices: CAD modeling, simulations.

Global opportunities in foreign-flagged vessels, coastal trading, DP ships.

Salaries and Compensation

Salaries vary by rank, vessel type, nationality, and company. Indian engineers (example):

| Rank | Monthly Salary (USD) | Annual Equivalent (USD) | Typical Vessel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fifth Engineer | 350-800 | 4,200-9,600 | Entry-level tankers |

| Fourth Engineer | 1,500-3,000 | 18,000-36,000 | Container ships |

| Third Engineer | 3,000-5,000 | 36,000-60,000 | Bulk carriers |

| Second Engineer | 5,000-8,000 | 60,000-96,000 | LNG carriers |

| Chief Engineer | 7,000-13,000 | 84,000-156,000 | Large cruise/offshore |

U.S. averages: $96,140 annually ($46.22/hour). Bonuses, overtime, and benefits add 20-50%. Tax-free for international contracts.

Related Engineering Disciplines

Marine engineering intersects with:

- Naval Architecture: Vessel form and stability.

- Ocean Engineering: Offshore structures, wave energy.

- Mechanical Engineering: Propulsion design.

- Electrical/Robotics: UUVs, cabling.

- Civil/Coastal: Ports, breakwaters.

- Petroleum: Rig integration.

Specific Challenges in Marine Engineering

The ocean is an unforgiving environment—constant motion, saltwater, extreme pressures, and biological growth create relentless threats to vessels and structures. Marine engineers must design, operate, and maintain systems that survive these forces for decades. Below are the core challenges, explained clearly with real engineering solutions and specifications.

1. Hydrodynamic Loading

Waves slam into ships millions of times over their lifetime, creating dynamic pressure spikes.

Impact: Structural fatigue, hull deformation, or cracking if not accounted for.

Solution:

- Use Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to model stress distribution.

- Design hull plating for 100 MPa cyclic loading (typical wave-induced stress).

- Add longitudinal stiffeners and double-bottom construction to absorb energy.

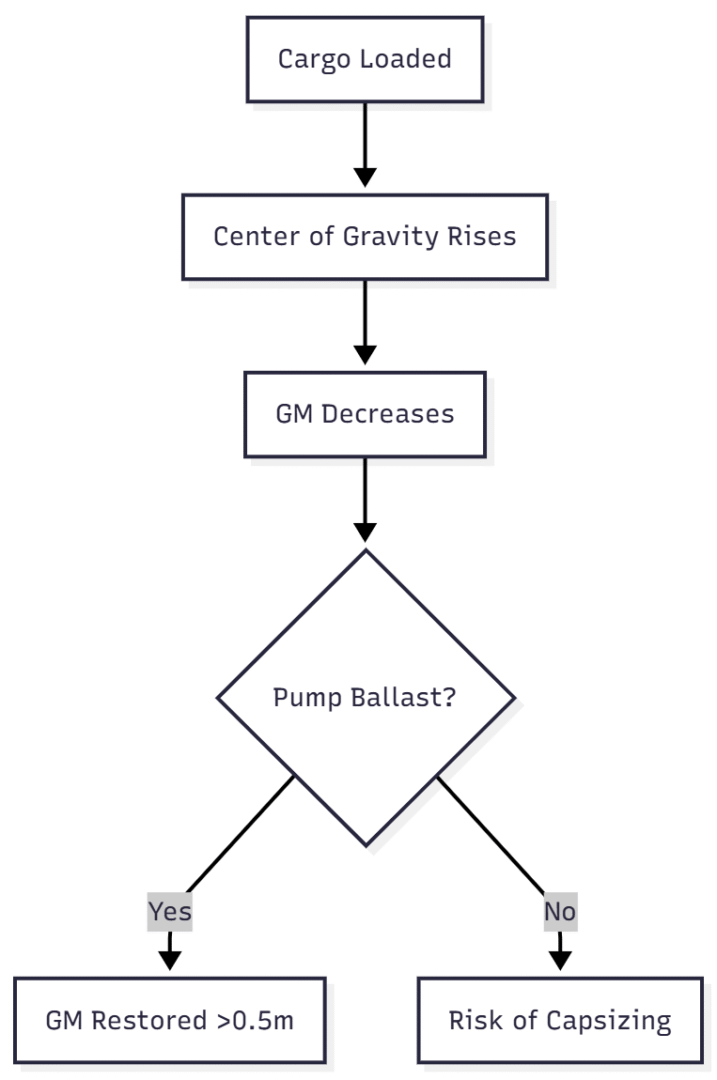

2. Stability

Ships must float upright even when cargo or fuel shifts.

Key Metric: Metacentric Height (GM) > 0.5 m (minimum for safe operation).

Risk: Low GM → capsizing (e.g., Costa Concordia).

Solution:

- Ballast water tanks automatically adjust weight distribution.

- Anti-heeling systems pump water side-to-side in <2 minutes.

- Real-time loading computers calculate GM before sailing.

3. Corrosion

Saltwater accelerates metal decay via electrochemical reactions.

Annual cost: ~$2.5 billion in ship repairs globally.

Solutions:

| Method | How it Works | Specs |

|---|---|---|

| Sacrificial Anodes | Zinc/aluminum corrodes instead of steel | Potential: -1.05 V (Zn) vs. Ag/AgCl |

| Impressed Current (ICCP) | DC current reverses corrosion | 10–50 A/m² hull current |

| Marine Coatings | Epoxy + polyurethane layers | 300–500 μm thickness, 10+ year life |

Pro Tip: ICCP systems auto-adjust current based on salinity and speed.

4. Anti-Fouling (Biofouling)

Barnacles, algae, and mussels grow on hulls → +40% fuel consumption.

Solutions:

- Electro-chlorination: Injects 0.5–2 ppm sodium hypochlorite into cooling water → kills larvae.

- Biocide Paints (TBT-free): Release copper ions at 2–5 μg/cm²/day.

- Silicone Foul-Release Coatings: Ultra-smooth surface → organisms slide off at >15 knots.

5. Pollution Control

Regulations: MARPOL Annex I & VI

Key Systems:

| Pollutant | Limit | Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Bilge Oil | <15 ppm | Oily Water Separator (gravity + coalescer) |

| SOx Emissions | 0.5% (global) | Exhaust Gas Scrubbers (90%+ reduction) |

| NOx | Tier III | SCR (Selective Catalytic Reduction) |

6. Cavitation

Low-pressure zones behind fast-spinning propellers form vapor bubbles → collapse → erode blades.

Damage: Pitting up to 5 mm deep in 1 year.

Prevention:

- Limit propeller tip speed < 30 m/s.

- Use 5–7 blades → lower RPM for same thrust.

- Apply cavitation-resistant coatings (e.g., nickel-aluminum bronze).

Submarine Advantage: More blades = quieter + less cavitation = harder to detect.

Industry Growth and Future Outlook

Projected 12% growth (2016-2026), adding 1,000 U.S. jobs. Drivers: Trade volume, offshore energy, sea-level rise adaptations. Innovations: Hydrogen fuel cells, zero-emission vessels by 2050 targets.

Marine engineering demands expertise in diverse systems while navigating environmental and operational complexities. From propulsion specifications to salary benchmarks, the field offers rewarding paths for those committed to maritime advancement. With continuous technological integration, marine engineers will lead sustainable ocean exploitation.

Frequently Asked Questions

A marine engineer operates, maintains, and repairs onboard systems (engines, power, HVAC, hydraulics). A naval architect designs the ship’s hull, stability, and overall structure. They work together: architect draws the ship; engineer makes it run.

6–8 years total:

4-year B.Eng/B.S. in Marine Engineering

6 months as Junior/Trainee

3–4 years sea time + Class IV → III → II exams

Class I certificate → Chief Engineer Fastest: 5 years with accelerated cadetship.

A 300m container ship (15,000 TEU) burns 180–250 tons of IFO 380 per day at 20 knots. Slow steaming (16 knots) drops it to 100–130 tons. That’s $60,000–$150,000/day at $600/ton.

Yes — 50% do:

Ship design offices (CAD/FEA)

Offshore wind/rig projects

Classification societies (DNV, ABS)

Shipyard supervision

Consultancy (emissions, retrofits) Same degree, no sea time required.

Yes, but controlled. Top risks:

Fire in engine room (CO₂ release in 60 sec)

Enclosed space entry (O₂ <19.5% = death)

High-voltage shock (6.6 kV switchboards) Mitigated by: Drills, permits, PPE, and strict ISM Code rules. Fatality rate: <1 per 100,000 sea days (safer than fishing).

Conclusion

Marine engineering powers global trade, defense, and renewable ocean energy through precision design, relentless maintenance, and real-time problem-solving. From countering corrosion with ICCP systems to optimizing fuel at 195 g/kWh, engineers ensure vessels survive decades of waves, salt, and storms. With salaries up to $156,000 tax-free and 12% job growth projected, the field rewards resilience and skill. Whether at sea or ashore, marine engineers don’t just maintain machines—they safeguard lives, commerce, and the environment. Master the systems, pass the exams, endure the contracts, and you command one of engineering’s most vital and demanding disciplines.

Happy Boating!

Share Marine Engineering with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Marine Propulsion Systems until we meet in the next article.