Emergencies on Ships

Maritime emergencies are critical events that demand swift, coordinated responses to protect lives, property, and the marine environment. Ships, whether commercial, passenger, or recreational, operate in an inherently hazardous domain where unpredictable conditions like severe weather, mechanical failures, or human errors can escalate into life-threatening situations. This article provides an in-depth exploration of shipboard emergencies, detailing their types, response strategies, regulatory frameworks, training requirements, and essential equipment. By understanding these elements, maritime professionals can enhance preparedness, mitigate risks, and ensure compliance with international standards. This guide aims to serve as a definitive resource for ship operators, crew members, and safety officers navigating the complexities of emergencies at sea.

The Nature of Shipboard Emergencies

The maritime environment is dynamic and unforgiving. Isolated from immediate external support, ships must rely on onboard resources and crew expertise to manage crises. Emergencies can disrupt operations, endanger lives, and cause environmental harm. The key to effective management lies in structured protocols, rigorous training, and advanced technology. From fires in engine rooms to medical emergencies far from shore, each scenario requires specific actions tailored to the vessel type and situation. The following sections outline the primary types of emergencies, their causes, and immediate response measures, ensuring a thorough understanding of maritime safety challenges.

Types of Ship Emergencies

Emergencies on ships vary in origin, impact, and complexity. Below is a detailed examination of the most prevalent types, informed by maritime safety data and industry standards.

1. Fire and Explosion

Fires are among the most dangerous shipboard emergencies, often originating in high-risk areas like engine rooms, cargo holds, or crew accommodations. They can result from fuel leaks, electrical faults, or mishandling of flammable materials. Explosions may follow if fires ignite volatile substances, such as fuel tanks or hazardous cargo.

- Engine Room Fires: These account for approximately 50% of ship fires, driven by oil leaks, overheating machinery, or hydraulic failures. The confined space and abundance of ignition sources make engine rooms particularly vulnerable.

- Cargo Hold Fires: Common in vessels carrying flammable or chemical goods, these fires can escalate due to self-ignition or chemical reactions.

- Accommodation Fires: Caused by faulty appliances, smoking violations, or electrical short circuits.

Response Measures:

- Sound the fire/general alarm immediately.

- Inform the officer on watch and muster crew per the fire muster list.

- Activate fire suppression systems (e.g., CO2, foam).

- Seal affected compartments to starve the fire of oxygen.

- Evacuate non-essential personnel to safe zones.

Key Considerations:

- Engine room fires require rapid isolation to prevent spread.

- Cargo fires involving hazardous materials follow the Emergency Schedules (EmS) Guide for dangerous goods.

2. Flooding and Water Ingress

Flooding occurs when water enters the ship through hull breaches, internal leaks, or severe weather, threatening stability and potentially leading to sinking.

- Hull Breaches: Result from collisions, groundings, or structural corrosion.

- Internal Leaks: Caused by faulty plumbing, valves, or ballast systems.

- Weather-Induced Flooding: High waves or storms can overwhelm deck hatches or cause structural damage.

Response Measures:

- Close watertight doors to limit water spread.

- Activate bilge pumps to remove ingress.

- Conduct emergency repairs to patch breaches.

- Monitor stability to prevent capsizing.

Key Considerations:

- Flooding alters the ship’s center of gravity, requiring careful management.

- Real-time tools like the NAPA Emergency Computer can assess damage and predict survivability.

3. Collisions and Groundings

Collisions involve impacts with other vessels, icebergs, or infrastructure, while groundings occur when a ship runs aground on reefs, sandbanks, or shallows. Both can cause hull damage and flooding.

- Navigational Errors: Often due to human error, poor visibility, or radar failure.

- Environmental Factors: Fog, strong currents, or high traffic in shipping lanes increase risks.

- Structural Impacts: Breaches can compromise watertight integrity.

Response Measures:

- Sound the general alarm and muster crew.

- Assess damage and check for flooding.

- Send distress signals via GMDSS (Global Maritime Distress and Safety System).

- Deploy emergency anchoring to stabilize the vessel.

Key Considerations:

- High-traffic areas like port entrances demand heightened vigilance.

- Post-incident, preserve evidence for investigations.

4. Mechanical Failures

Mechanical failures, such as engine breakdowns, steering loss, or power outages, can leave a ship adrift, especially dangerous in rough seas.

- Engine Failure: Caused by fuel contamination, overheating, or mechanical wear.

- Steering Gear Issues: Hydraulic or linkage failures impair navigation.

- Electrical Outages: Generator faults disable critical systems like pumps or navigation.

Response Measures:

- Switch to backup systems or emergency generators.

- Attempt manual steering if automated systems fail.

- Secure the vessel and prepare for drift.

- Inform crew and nearby vessels of the situation.

Key Considerations:

- Regular maintenance reduces failure risks.

- Backup systems are critical for operational continuity.

5. Man Overboard (MOB)

MOB incidents occur when a crew member or passenger falls overboard, risking drowning, hypothermia, or injury.

- Causes: Rough seas, inadequate railings, or accidents during work or leisure.

- Risks: Cold water shock and difficulty in locating the individual.

Response Measures:

- Sound the MOB alarm and throw lifebuoys.

- Alert nearby vessels and deploy rescue boats.

- Maneuver the ship to maintain visual contact and facilitate recovery.

Key Considerations:

- Speed is critical; hypothermia sets in quickly in cold waters.

- Training ensures crew can execute rescue operations efficiently.

6. Piracy and Armed Robbery

In high-risk areas like the Gulf of Aden or Southeast Asia, pirates may board ships to steal cargo, kidnap crew, or seize vessels.

- Vulnerabilities: Slow-moving or low-freeboard ships are prime targets.

- High-Risk Areas: Specific maritime regions require heightened security.

Response Measures:

- Increase lookouts and vigilance.

- Use defensive measures like water cannons or citadels.

- Coordinate with naval forces for escorts or support.

Key Considerations:

- Best Management Practices (BMP) reduce risks.

- Crew training in anti-piracy tactics is essential.

7. Medical Emergencies

Medical crises at sea, such as injuries, illnesses, or outbreaks, are challenging due to limited access to advanced care.

- Common Issues: Slips, falls, machinery injuries, or disease flare-ups.

- Resource Constraints: Ships carry basic medical kits and rely on trained crew.

Response Measures:

- Administer first aid using onboard kits (basic kits cost $500-$2000).

- Use telemedicine for shore-based guidance.

- Arrange medevac by helicopter or speedboat if critical.

Key Considerations:

- Crew must be trained in first aid and CPR.

- Defibrillators and trauma kits are vital.

8. Pollution Incidents

Spills of oil, chemicals, or ballast water can devastate marine ecosystems and incur legal penalties.

- Causes: Tanker breaches, cargo mishandling, or operational errors.

- Environmental Impact: Oil spills harm wildlife; ballast water introduces invasive species.

Response Measures:

- Deploy containment booms and absorbents.

- Notify authorities per MARPOL and SOPEP (Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan).

- Implement cleanup protocols.

Key Considerations:

- Compliance with international conventions is mandatory.

- Rapid response minimizes environmental damage.

9. Severe Weather and Natural Disasters

Storms, hurricanes, or tsunamis pose significant risks, causing structural damage or capsizing.

- Risks: High waves, ice accretion, or sudden tsunamis.

- Vessel Impact: Stability loss or equipment damage.

Response Measures:

- Adjust routes based on weather forecasts.

- Secure loose items and cargo.

- Monitor stability and log actions.

Key Considerations:

- Weather monitoring systems are critical.

- Crew must be trained in storm navigation.

To summarize, the following table outlines key emergency types, causes, and initial responses:

| Emergency Type | Primary Causes | Initial Actions | Key Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fire/Explosion | Fuel leaks, electrical faults | Sound alarm, activate suppression | Extinguishers, CO2 systems |

| Flooding | Hull breaches, leaks | Close doors, activate pumps | Bilge pumps, watertight seals |

| Collision/Grounding | Navigation errors, environment | Assess damage, signal distress | Anchors, pumps |

| Mechanical Failure | Breakdowns | Use backups, secure vessel | Emergency generators |

| Man Overboard | Falls | Throw buoys, deploy rescue | Lifebuoys, rescue boats |

| Piracy | Attacks | Increase lookouts, use defenses | Water cannons, citadels |

| Medical | Injuries, illnesses | Administer first aid, contact support | Medical kits, defibrillators |

| Pollution | Spills | Contain release, notify authorities | Booms, absorbents |

| Severe Weather | Storms | Reduce speed, secure items | Stability logs, weather monitors |

This table underscores the diversity of emergencies and the need for tailored responses.

Emergency Response Protocols

Effective emergency management hinges on calm, structured actions. Panic or hasty decisions can exacerbate situations, making training and preparedness paramount.

General Emergency Protocol

Upon detecting an emergency:

- Sound the general alarm to alert all crew.

- Muster at designated stations per the muster list.

- Inform the officer on watch and the master.

- Assess the situation and report findings.

Specific Response Protocols

Each emergency type requires distinct actions:

- Fire:

- Raise fire alarm and muster per fire list.

- Activate appropriate extinguishers based on fire class (e.g., water for Class A, CO2 for Class C).

- Close fire doors and activate suppression systems.

- Example: For a galley fire, isolate electrical systems and use CO2 smothering.

- Flooding:

- Close watertight doors to contain water.

- Activate bilge pumps and monitor water levels.

- Attempt temporary patches on breaches.

- Collision/Grounding:

- Sound general alarm and send distress signals.

- Assess hull damage and initiate pumping if needed.

- Deploy anchors to stabilize.

- Mechanical Failure:

- Switch to emergency generators or manual steering.

- Secure the vessel and prepare for drift.

- Notify nearby vessels for assistance.

- Man Overboard:

- Sound MOB alarm and throw lifebuoys.

- Deploy rescue boats and maintain visual contact.

- Use signals (e.g., one long whistle, three short) to alert others.

- Piracy:

- Increase lookouts and activate defensive measures.

- Retreat to citadels if boarding occurs.

- Contact naval forces via distress channels.

- Medical:

- Provide immediate first aid using onboard kits.

- Contact shore-based medical support via telemedicine.

- Arrange evacuation for critical cases.

- Pollution:

- Deploy containment equipment per SOPEP.

- Notify authorities and document actions.

- Use absorbents to minimize spread.

- Severe Weather:

- Reduce speed and secure loose items.

- Monitor stability and adjust course.

- Maintain detailed logs for post-incident review.

The EmS Guide, aligned with the IMDG Code, provides specific protocols for dangerous goods incidents, emphasizing tailored responses based on cargo type and stowage location.

IS-SAFE Schema for Structured Response

The IS-SAFE schema, inspired by IMO Resolution A.1072(28), provides a modular framework for emergency response:

- I: Immediate assessment (raise alarms, gather data).

- S: Shoreside initiation (send distress signals, alert company).

- S: Substantial control (deploy teams, activate systems).

- A: Additional reporting (update coastguard, insurers).

- F: Follow-up (ventilate spaces, reset systems).

- E: Evolution to post-emergency (file non-conformity reports, investigate).

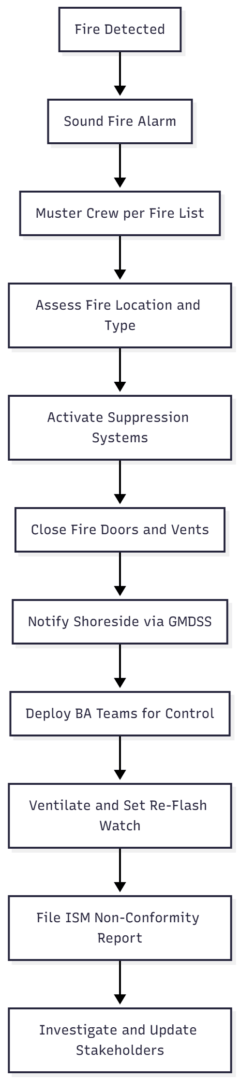

Here’s a flowchart illustrating the IS-SAFE process for a fire emergency:

This flowchart ensures sequential, harmonized actions.

Example: Galley Fire Response:

- Immediate: Raise alarm, activate pumps, maneuver to expel fumes.

- Shoreside: Send Mayday, alert company per ISM S8.3.

- Substantial: Deploy BA teams, use CO2 hood system, isolate power.

- Additional: Downgrade to Pan-Pan, inform SOPEP contacts.

- Follow-Up: Ventilate, reset systems, monitor for re-ignition.

- Evolution: Report to insurers, preserve VDR data.

Example: Engine Room Fire:

- Immediate: Raise alarm, energize emergency generator, close doors.

- Shoreside: Initiate Mayday, activate company response.

- Substantial: Shut vents, deploy CO2, isolate fuel valves.

- Additional: Update coastguard, notify flag state.

- Follow-Up: Expel gases, reset systems.

- Evolution: File reports, brief stakeholders.

Regulatory Frameworks and International Standards

Maritime safety is governed by robust international regulations ensuring uniform practices across fleets.

SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea)

Adopted post-Titanic, SOLAS sets standards for ship construction, equipment, and operations. Chapter III, Regulation 19 mandates:

- Familiarity with safety equipment before voyages.

- Monthly fire and abandon ship drills, including:

- Lifeboat lowering and engine operation.

- Checking life jackets and muster duties.

- Enclosed space entry drills every two months.

Fire protection per SOLAS:

- Class A (Solids): Water cools and extinguishes.

- Class B (Liquids): Foam or dry chemical smothers.

- Class C (Gases): CO2 displaces oxygen.

- Class D (Metals): Dry powder absorbs heat.

- Class F (Oils): Wet chemical for saponification.

Passive systems include bulkheads:

- A-60: 60-minute fire resistance, steel with insulation ($500-$2000/m²).

- B-15: 15-minute flame resistance.

Active systems:

- Extinguishers: CO2 (5kg, ~$100-$250), foam (9L, ~$80-$200).

- Sprinklers and water mist systems ($10,000+ for installation).

ISM Code (International Safety Management)

Incorporated into SOLAS Chapter IX post-Herald of Free Enterprise, the ISM Code mandates Safety Management Systems (SMS) to:

- Ensure safe operations and environmental protection.

- Assess risks and establish safeguards.

- Require procedures for emergency preparedness, reporting, and audits.

SMS components:

- Safety policies.

- Clear communication lines.

- Incident reporting protocols.

- Regular training and drills.

STCW (Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping)

STCW ensures crew competency through standardized training, including:

- Basic safety and fire-fighting.

- Proficiency in English for SMCP.

- Certification for deck officers to manage drills.

IMO Guidelines and EmS

IMO Resolution A.1072(28) promotes integrated contingency planning. The EmS Guide addresses fires and spills involving dangerous goods, specifying responses based on cargo type and stowage.

Standard Marine Communication Phrases (SMCP)

SMCP standardizes distress communication:

- Mayday: Immediate danger (e.g., fire, sinking).

- Pan-Pan: Urgency (e.g., mechanical failure).

- Whistle Signals:

- One short: Starboard turn.

- Two short: Port turn.

- Five short: Danger warning.

- One long, three short: MOB.

- Six short, one long: General emergency.

Training and Drills: Building Competence

Regular training and drills are critical for preparedness. SOLAS mandates:

- Monthly fire and abandon ship drills, conducted as if real.

- Enclosed space drills bimonthly for relevant crew.

Fire Drills

- Simulate scenarios (e.g., engine room fire).

- Check fireman’s outfits, pumps, and communication.

- Test watertight doors and ventilation systems.

Abandon Ship Drills

- Summon crew to muster stations.

- Verify life jacket use and lifeboat readiness.

- Practice launching and operating lifeboats.

Muster lists, displayed prominently, outline duties for each crew member.

Fire Theory and Hazards

Understanding fire theory is foundational:

- Fire Tetrahedron: Fuel, heat, oxygen, chain reaction.

- Extinguishing: Remove one element (e.g., CO2 displaces oxygen).

Key hazard areas:

- Engine Room: 70% of fires from oil leaks.

- Galley: Cooking oils ignite easily.

- Cargo Holds: Flammable goods pose risks.

Training includes creating informational posters to reinforce knowledge.

Essential Equipment and Systems

Effective emergency response relies on reliable equipment.

Fire-Fighting Equipment

- Portable Extinguishers:

- Dry chemical ($50-$150): For Classes A, B, C; smothers fires.

- CO2 ($100-$250): For Classes B, C; displaces oxygen.

- Foam ($80-$200): For engine rooms; smothers without damage.

- Specs: 5-23kg, equivalent to 9L fluid.

- Fixed Systems:

- CO2: Fills compartments to reduce oxygen ($10,000+ systems).

- Water Mist: Cools fires ($15,000+).

- High-Expansion Foam: Smothers large spaces ($20,000+).

Life-Saving Appliances

- Life jackets ($50-$200) and rafts ($5000-$15,000).

- Rescue boats and lifebuoys ($20-$100).

Detection and Monitoring

- Flood sensors for automatic detection.

- NAPA Emergency Computer ($10,000-$50,000): Provides real-time stability and survivability data, with TRIAGE categorization (green: safe; red: high risk).

Maintenance

SOLAS requires:

- Weekly inspections of extinguishers and detectors.

- Annual servicing of fixed systems.

- Drill-based testing to identify defects.

Table of Fire Extinguishing Agents:

| Fire Class | Fuel Type | Preferred Agent | Mechanism | Approx. Price (Portable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Solids | Water | Cooling | $50-$100 |

| B | Liquids | Foam/Dry Chemical | Smothering | $80-$150 |

| C | Gases | CO2 | Displacement | $100-$200 |

| D | Metals | Dry Powder | Absorption | $150-$250 |

| F | Oils/Fats | Wet Chemical | Saponification | $100-$180 |

Real-Time Emergency Management Tools

Advanced systems enhance response efficiency:

- NAPA Emergency Computer: Monitors flooding, predicts survivability over 3.5 hours, and provides advisory cards for crew guidance.

- NAPA Fleet Intelligence: Syncs real-time data with shoreside teams, enabling rapid strategic decisions.

- TRIAGE System: Color-codes risk (green: no risk; red: high risk).

Benefits:

- Automatic damage detection via sensors.

- Real-time stability updates.

- Shoreside alerts for coordinated response.

Case Studies and Lessons Learned

Historical incidents highlight the importance of preparedness:

- Titanic (1912): Led to SOLAS, emphasizing lifeboats and drills.

- Herald of Free Enterprise (1987): Prompted ISM Code for SMS.

Modern practices:

- Use SOPEP for pollution incidents.

- Preserve VDR data for investigations.

Best Practices for Maritime Safety

- Training: Conduct regular, realistic drills.

- Equipment: Maintain and test all systems.

- Communication: Use SMCP for clear distress signals.

- Technology: Leverage tools like NAPA for real-time insights.

- Compliance: Adhere to SOLAS, ISM, and STCW.

Conclusion

Emergencies on ships demand proactive preparation, structured responses, and adherence to international standards. By understanding emergency types, implementing protocols like IS-SAFE, and leveraging technology, maritime operators can minimize risks. Continuous training, robust equipment, and clear communication are the cornerstones of safety at sea, ensuring crews navigate challenges with confidence and competence.

Happy Boating!

Share Emergencies on Ships with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read New Boat Lift Images 4K HD Wallpapers until we meet in the next article.