Can sailboats sail in all directions?

Discover how sailboats navigate all directions using wind, tacking, and points of sail. Learn techniques and boat designs for optimal sailing.

Sailboats captivate with their ability to glide across water, powered solely by the wind. A common question among novice and seasoned sailors alike is: Can sailboats sail in all directions? The answer is nuanced. While sailboats cannot sail directly into the wind due to a “no-go zone” spanning about 45 degrees on either side of the wind direction, they can navigate virtually any direction using techniques like tacking and jibing, combined with an understanding of points of sail, boat design, and wind dynamics. This comprehensive guide explores how sailboats achieve this, delving into sailing techniques, boat designs, challenges, and the role of technology.

Understanding the Basics: Why Sailboats Can’t Sail Directly Into the Wind

Sailboats rely on wind interacting with their sails to generate lift, propelling the boat forward. When a sailboat faces directly into the wind, the sails luff (flap uncontrollably), losing their ability to generate lift. This creates the no-go zone, an area approximately 45 degrees on either side of the true wind direction where forward movement is impossible. To overcome this limitation, sailors employ a zigzagging maneuver called tacking to sail upwind indirectly.

The No-Go Zone Explained

The no-go zone, also known as being “in irons,” occurs because the wind’s force cannot be harnessed when the boat’s bow points directly into it. Attempting to sail in this zone stalls the boat, as the sails cannot maintain an aerodynamic shape. The size of the no-go zone varies slightly depending on the boat’s design, sail configuration, and wind conditions, but 45 degrees is a standard benchmark for most modern sailboats.

Points of Sail: Navigating Different Wind Angles

To sail in various directions, sailors adjust their course and sails according to the points of sail, which describe the boat’s angle relative to the wind. Each point of sail requires specific sail trim and steering techniques to optimize speed and stability. Below is a detailed breakdown of the primary points of sail:

1. Close-Hauled

- Angle to Wind: 30–45 degrees

- Description: The closest a sailboat can sail to the wind without entering the no-go zone. Sails are trimmed tightly to create a streamlined shape, maximizing lift.

- Use: Essential for sailing upwind, often combined with tacking to reach an upwind destination.

- Example: A sloop racing upwind adjusts sails to a tight angle, maintaining a course about 40 degrees off the true wind.

2. Close Reach

- Angle to Wind: 45–60 degrees

- Description: Slightly further from the wind than close-hauled, allowing for more relaxed sail trim and increased speed.

- Use: Offers a balance of speed and stability, ideal for making progress toward an upwind target without frequent tacking.

- Example: A cruising yacht on a close reach sails comfortably, with sails eased slightly for efficiency.

3. Beam Reach

- Angle to Wind: 90 degrees

- Description: The wind blows directly across the boat’s beam (side), with sails let out halfway. This is often the fastest and most stable point of sail.

- Use: Preferred for leisurely cruising or covering long distances efficiently.

- Example: A catamaran on a beam reach glides smoothly, harnessing maximum wind power.

4. Broad Reach

- Angle to Wind: 120–150 degrees

- Description: The wind comes from behind at an angle, filling the sails from the rear. Sails are let out further to capture more wind.

- Use: Provides exhilarating speed but requires caution to avoid accidental jibing.

- Example: A trimaran on a broad reach surges forward, with sails adjusted to prevent sudden boom swings.

5. Running (Downwind)

- Angle to Wind: 180 degrees

- Description: The wind blows directly from behind, with sails spread out like wings or a spinnaker deployed for maximum surface area.

- Use: Offers high speed but can be unstable, requiring careful control to prevent jibing or rolling.

- Example: A schooner running downwind uses a spinnaker to capture wind, maintaining a steady course.

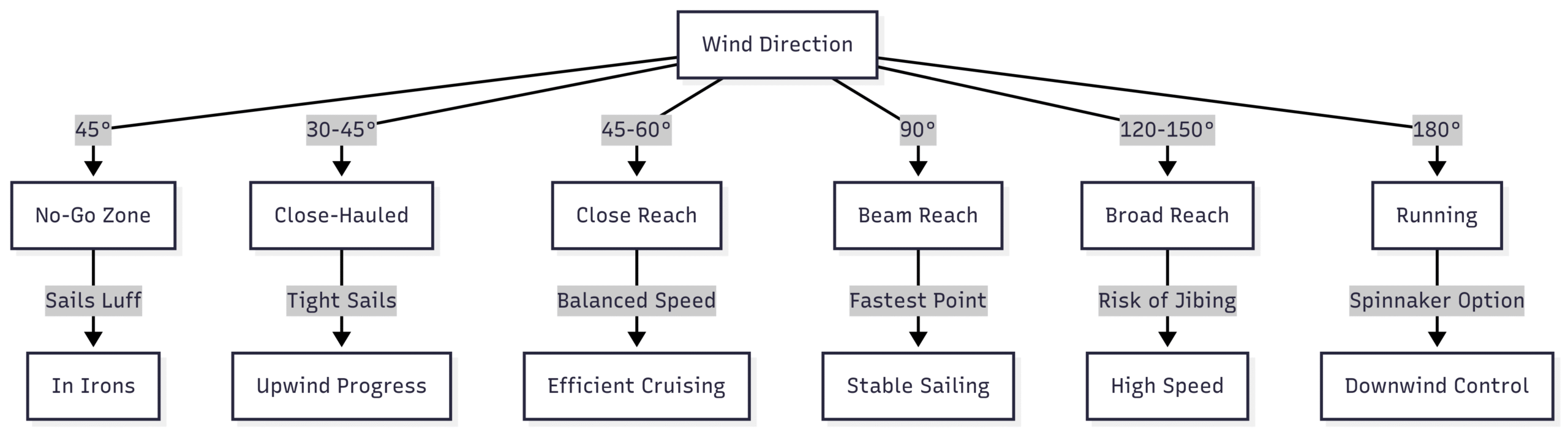

Chart: Points of Sail

This chart illustrates how each point of sail relates to the wind direction and the associated sailing dynamics.

Tacking and Jibing: Key Maneuvers for Directional Control

To sail upwind or change direction downwind, sailors use two critical maneuvers: tacking and jibing.

Tacking

- Definition: Turning the boat’s bow through the wind, switching the wind from one side of the sails to the other.

- Process: The helmsman steers the boat into the wind, and the crew adjusts the sails to fill on the opposite side. This allows the boat to zigzag upwind.

- Example: A sailor tacking a sloop turns the bow through the no-go zone, alternating between 40 degrees on port and starboard tacks to reach an upwind mark.

Jibing

- Definition: Turning the boat’s stern through the wind, typically when sailing downwind, causing the sails to switch sides.

- Process: The crew carefully controls the boom to prevent it from swinging violently across the boat, which can be dangerous.

- Example: A ketch jibing downwind adjusts the mainsail and jib to opposite sides, maintaining control to avoid an accidental jibe.

These maneuvers enable sailors to navigate any direction by iteratively adjusting their course relative to the wind.

Boat Design and Its Impact on Sailing Directions

A sailboat’s ability to sail various directions depends heavily on its design, including hull shape, keel configuration, and sail rigging. Different designs are optimized for specific points of sail, as outlined in the table below:

| Boat Type | Hull Shape | Keel Configuration | Optimized Sailing Direction | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sloop | V-shape | Fin keel | Upwind | Narrow beam, deep keel for close-hauled sailing |

| Cutter | V-shape | Fin keel | Upwind | Multiple headsails for versatility |

| Ketch | Round or flat-bottomed | Full keel/centerboard | Across the wind | Balanced sail area for beam reach |

| Yawl | Round or flat-bottomed | Full keel/centerboard | Across the wind | Mizzen sail for stability |

| Catamaran | Flat-bottomed | Daggerboards or skegs | Downwind | Wide beam, large sail area for speed |

| Trimaran | Flat-bottomed | Daggerboards or skegs | Downwind | Enhanced stability for broad reach |

| Schooner | V-shape or round | Full keel/centerboard | Upwind | Multiple masts for efficient upwind sailing |

Hull Shape

- V-shape: Cuts through water efficiently, ideal for upwind sailing (e.g., sloops, cutters).

- Flat-bottomed: Provides stability and speed, suited for downwind sailing (e.g., catamarans, trimarans).

- Round: Balances speed and maneuverability, versatile for beam reach (e.g., ketches, yawls).

Keel Configuration

- Fin Keel: Reduces leeway, enabling close-hauled sailing.

- Full Keel/Centerboard: Offers stability for beam reach and broad reach.

- Daggerboards/Skegs: Enhance downwind performance by minimizing drag.

Sail Rigging

Sail configurations determine how effectively a boat harnesses wind at different angles. Common rigs include:

| Rig Type | Sail Arrangement | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sloop | 1 mast, 1 mainsail, 1 jib | Easy to handle, good upwind performance | Limited sail area for downwind |

| Cutter | 1 mast, 1 mainsail, 2+ headsails | Versatile, strong upwind | Complex to manage |

| Ketch | 2 masts, mainsail, mizzen, headsails | Balanced, efficient across the wind | Less effective upwind/downwind |

| Yawl | 2 masts, mainsail, mizzen, headsails | Stable, good for beam reach | Similar to ketch, less efficient upwind |

Modern sloops and cutters, priced between $50,000–$500,000 for recreational models (e.g., Beneteau Oceanis 40.1, ~$250,000), dominate due to their simplicity and upwind efficiency. Ketches and yawls, ranging from $100,000–$1,000,000 (e.g., Amel 50, ~$900,000), are favored for long-distance cruising.

Apparent vs. True Wind: A Critical Distinction

A key factor in sailing direction is the difference between true wind (the wind’s actual direction and speed) and apparent wind (the wind felt on the moving boat, influenced by the boat’s speed and direction). Faster boats, like racing catamarans, generate higher apparent wind speeds, allowing them to sail closer to the true wind direction—sometimes as low as 30–35 degrees true wind angle (TWA).

Example: True vs. Apparent Wind

- Scenario: A Melges 32 racing at 14 knots true wind speed (TWS) achieves a TWA of 34 degrees with a velocity made good (VMG) of 5.79 knots.

- Explanation: The boat’s speed shifts the apparent wind forward, reducing the apparent wind angle (AWA) to ~25–30 degrees, enhancing upwind efficiency.

This distinction often sparks debates, as seen in online sailing forums, where sailors argue whether modern boats can sail closer than 45 degrees to the true wind. High-performance racers (e.g., Gunboat 60, ~$2,000,000) can achieve 35–40 degrees TWA, while cruisers typically hover around 45 degrees.

Challenges in Sailing Any Direction

Sailing in all directions presents several challenges, influenced by environmental and navigational factors:

1. Opposing Winds

- Challenge: Winds blowing from the desired direction force tacking, increasing travel distance and time.

- Solution: Master tacking techniques and optimize sail trim to maintain VMG.

2. Tides and Currents

- Challenge: Strong currents can push the boat off course, especially in coastal or tidal waters.

- Solution: Plan routes using tide tables and current charts, adjusting course to compensate.

3. Navigational Hazards

- Challenge: Rocks, shoals, and other obstacles can restrict safe sailing paths.

- Solution: Use electronic charts and GPS to avoid hazards, ensuring safe navigation.

Technology’s Role in Enhancing Sailing Capabilities

Modern technology significantly improves a sailboat’s ability to navigate any direction safely and efficiently:

- GPS Navigation: Systems like Garmin GPSMAP 86i (~$600) provide precise location data, aiding route planning and hazard avoidance.

- Weather Forecasting: Apps like PredictWind (~$20/month) deliver real-time weather updates, helping sailors anticipate wind shifts.

- Autopilot Systems: Raymarine Evolution Autopilot (~$2,000) reduces crew fatigue, maintaining consistent courses during long passages.

- Communication: VHF radios (e.g., Icom M330, ~$200) ensure contact with other vessels and authorities.

- Safety Equipment: EPIRBs (e.g., ACR GlobalFix V4, ~$500) enhance emergency response capabilities.

These tools empower sailors to tackle challenging conditions and navigate restricted waters, such as harbors or channels, where local regulations may dictate specific routes.

Historical Perspective: Evolution of Upwind Sailing

The ability to sail upwind has evolved over centuries, driven by innovations in boat design and rigging:

- 6th Century: Vikings introduced keels, enabling beam and close reaches with square-rigged ships.

- 1st Century BC: Greeks adopted lateen sails, improving upwind performance.

- 16th–19th Centuries: Square-rigged ships used fore-and-aft sails to sail upwind, though limited to ~60–65 degrees TWA.

- Modern Era: Bermudan rigs and advanced hull designs allow 30–45 degrees TWA, with racing boats pushing below 35 degrees.

Polynesian canoes, dating back to 1200 BC, sailed close reaches without keels, relying on deep hulls for lateral resistance. Similarly, Captain Cook’s flat-bottomed ships demonstrated that hull shape alone could enable upwind sailing in certain conditions.

FAQs: Common Questions About Sailing Directions

What’s the Best Way to Learn Points of Sail?

- Study Theory: Use diagrams and resources like this article to understand wind angles.

- Join a Sailing Course: Enroll in programs like ASA 101 Basic Keelboat Sailing (~$500) for hands-on training.

- Practice: Sail on different boats in varied conditions to develop intuition for sail trim and steering.

What’s the Best Point of Sail?

- Depends on Goals:

- Racing: Close-hauled for upwind progress.

- Cruising: Beam reach for speed and comfort.

- Downwind Thrills: Broad reach or running with a spinnaker.

- Example: A beam reach is often favored for its balance, making it ideal for family sailing on a Beneteau First 36 (~$300,000).

Conclusion: Mastering the Art of Sailing Any Direction

Sailboats cannot sail directly into the wind, but with techniques like tacking and jibing, combined with an understanding of points of sail, boat design, and wind dynamics, sailors can navigate virtually any direction. Modern technology enhances these capabilities, while historical innovations like keels and lateen sails laid the foundation for today’s versatile sailboats. Whether you’re a novice learning to tack or a racer pinching at 35 degrees TWA, mastering these principles unlocks the freedom to explore the open sea.

Happy Boating!

Share Can sailboats sail in all directions? with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Can You Sail Anywhere in the World? Surprisingly, No until we meet in the next article.