Discover keel construction and design for sailboats, exploring types, materials, and benefits to choose the best keel for your sailing needs.

The keel is the backbone of any sailboat, a critical structural and hydrodynamic component that ensures stability, directional control, and performance on the water. While often overlooked by novice sailors, the keel’s design and construction significantly influence a boat’s handling, safety, and suitability for specific cruising grounds. This comprehensive guide explores keel types, materials, construction methods, and their impact on sailing performance, helping you choose the best keel design for your needs.

What is a Keel?

A keel is a longitudinal structural element running along the centerline of a boat’s hull, from bow to stern, typically at the vessel’s lowest point. It serves multiple purposes: providing stability, counteracting lateral forces from the wind, and enhancing directional control. On sailboats, the keel is essential for preventing excessive sideways drift (leeway) and ensuring the boat moves forward efficiently under sail. Beyond sailboats, keels are found on various watercraft, including cargo ships and smaller vessels, where they contribute to balance and structural integrity.

The term “keel” originates from the Old English cēol or Old Norse kjóll, meaning “ship” or “keel.” Historically, it was one of the first recorded words in English, noted by Gildas in the 6th century. The keel’s role as a vessel’s backbone has been recognized since ancient times, with evidence of rudimentary keels in shipwrecks like the Uluburun (c. 1325 BC) and the Kyrenia ship (c. 315 BC).

Functions of a Keel

The keel performs several critical functions that directly impact a sailboat’s performance and safety:

- Stability and Balance: The keel lowers the boat’s center of gravity, reducing the risk of capsizing by counteracting the heeling forces of wind on the sails. Ballast, often made of dense materials like lead, enhances this stability.

- Directional Control: Acting as an underwater foil, the keel provides lateral resistance, preventing leeway and allowing the boat to maintain its course, especially when sailing upwind.

- Structural Strength: The keel reinforces the hull, absorbing impacts from waves or grounding, and serves as the foundation for the boat’s framework in traditional construction.

- Improved Sailing Performance: By generating lift, similar to an aircraft wing, the keel enhances upwind performance and ensures efficient forward motion.

Key Keel Terminology

Understanding keel design requires familiarity with specific terms:

- Root: The top of the keel where it attaches to the hull.

- Tip: The bottommost part of the keel, ideally kept clear of the seabed.

- Chord: The keel’s width when viewed from the side. A short-chord keel is deep and narrow, while a long-chord keel is shallow and extends further along the hull.

- Draft: The depth of the keel below the waterline, affecting the boat’s ability to navigate shallow waters.

- Ballast: Heavy material (e.g., lead or iron) placed in the keel to enhance stability.

Types of Keels and Their Applications

Keel designs vary widely, each tailored to specific sailing purposes, from coastal cruising to offshore racing. Below is a detailed breakdown of common keel types, their characteristics, and their ideal uses.

1. Full Keel

Description: A full keel extends along most of the hull’s length, often with a cutaway forefoot for improved maneuverability. It is typically integrated into the hull and heavily ballasted.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Moderate to deep (2–3 meters for larger yachts).

- Materials: Often lead ballast encased in fiberglass or GRP (glass-reinforced plastic).

- Stability: Excellent, with a low center of gravity.

- Maneuverability: Moderate; less responsive than fin keels but excellent for directional stability.

Applications: Ideal for long-distance offshore cruising due to its durability, stability, and comfortable motion in rough seas. The keel-hung rudder, often found on full keel designs, is less prone to damage from debris, making it popular among short-handed sailors using windvane self-steering systems.

Example: Rustler 36, a classic offshore cruiser with a long keel and cutaway forefoot, balances responsiveness with rock-solid reliability.

Pros:

- Superior directional stability.

- Robust construction reduces damage risk.

- Comfortable motion in heavy seas.

Cons:

- Increased drag reduces speed.

- Poor maneuverability in reverse under power.

2. Fin Keel

Description: A shorter, deeper keel bolted to the hull, often with a flared or bulbed tip to maximize ballast placement.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Deep (1.5–2.5 meters for coastal boats, deeper for racers).

- Materials: Lead or iron ballast, bolted to a GRP or composite hull.

- Stability: Good, with ballast concentrated low for stiffness.

- Maneuverability: Highly responsive, ideal for tacking and quick maneuvers.

Applications: Suited for coastal sailing and performance-oriented boats, such as the Rustler 33, designed for nimble handling and speed in coastal waters.

Pros:

- Low drag for higher speeds.

- Excellent maneuverability.

- Responsive helm for dynamic sailing.

Cons:

- Susceptible to snagging debris (e.g., fishing lines).

- Less directional stability than full keels.

3. Bulb Keel

Description: A fin keel with a heavy, torpedo-shaped bulb at the tip to concentrate ballast lower.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Moderate to deep (1.8–3 meters).

- Materials: Lead bulb with a GRP or metal fin.

- Stability: Excellent due to low center of gravity.

- Maneuverability: Good, though slightly less agile than standard fin keels.

Applications: Common in racing sailboats and performance cruisers needing speed and stability, such as offshore racers.

Pros:

- Low center of gravity enhances stability.

- Efficient upwind performance.

- Balances speed and safety.

Cons:

- Bulb can snag debris.

- Higher construction costs.

4. Wing Keel

Description: A fin keel with horizontal “wings” at the base, increasing lift and reducing draft.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Shallow to moderate (1–2 meters).

- Materials: Lead or iron with GRP or metal fins.

- Stability: Good, with wings enhancing lift.

- Maneuverability: Excellent for shallow-water cruising.

Applications: Popular in shallow cruising grounds like the Bahamas or Australia’s coastal waters, famously used in the 1983 America’s Cup-winning yacht Australia II.

Pros:

- Reduced draft for shallow waters.

- Improved lift for upwind sailing.

- Good stability with moderate ballast.

Cons:

- Complex design increases costs.

- Wings can trap debris.

5. Lifting or Swing Keel

Description: A retractable keel that can be raised or lowered, often housed in a keel box or stub.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Variable (e.g., 0.8–2.5 meters for Rustler 57 with lifting keel).

- Materials: Bronze, lead, or iron for the blade; GRP or lead stub.

- Stability: Moderate when raised; excellent when lowered.

- Maneuverability: Good, though mechanical components add complexity.

Applications: Ideal for versatile cruising in areas with varying water depths, such as the East Coast of England or Holland. The Rustler 57’s lifting keel reduces draft to 2 meters when raised, enhancing access to shallow anchorages.

Pros:

- Adjustable draft for shallow waters.

- Maintains performance when lowered.

- Versatile for diverse cruising grounds.

Cons:

- Mechanical complexity increases maintenance.

- Keel box may reduce interior space.

6. Twin or Bilge Keel

Description: Two keels positioned on either side of the hull, often used in tidal areas.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Shallow (0.8–1.5 meters).

- Materials: Lead, iron, or GRP.

- Stability: Excellent for grounding in tidal areas.

- Maneuverability: Moderate, with good roll resistance.

Applications: Common in coastal cruisers operating in tidal regions, allowing boats to rest upright during low tide.

Pros:

- Stable when grounded.

- Reduces rolling in choppy seas.

- Shallow draft for coastal cruising.

Cons:

- Increased drag reduces speed.

- Less efficient upwind performance.

7. Encapsulated Keel

Description: A keel molded as part of the hull, with ballast (usually lead) bonded inside.

Characteristics:

- Draft: Moderate (1.5–2.5 meters).

- Materials: GRP hull with lead ballast.

- Stability: Excellent due to integrated construction.

- Maneuverability: Good, though less agile than bolted fin keels.

Applications: Used in offshore cruisers like the Rustler 37 and 42 for maximum strength and safety.

Pros:

- Robust, bolt-free construction.

- Lower maintenance than bolted keels.

- Excellent for long-distance cruising.

Cons:

- Higher draft limits shallow-water access.

- Heavier than bolted keels.

Keel Materials and Their Properties

The choice of keel material affects performance, cost, and durability. Below is a comparison of common materials:

| Material | Density (kg/m³) | Cost | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | 11,340 | High | High density, low volume, corrosion-resistant with coating | Expensive, requires protective coating |

| Cast Iron | 7,800 | Moderate | Affordable, good weight for stability | Heavier, prone to rust |

| Steel | 7,850 | Moderate | Strong, durable, suitable for large boats | Susceptible to corrosion |

| Stainless Steel | 8,000 | High | Corrosion-resistant, strong | Lighter, less effective ballast |

| Carbon Fiber | 1,800 | Very High | Lightweight, strong, high performance | Very expensive, complex construction |

Lead is preferred for performance boats due to its density, allowing for thinner keels with less buoyancy and better stability. Iron is cost-effective but requires more volume, increasing drag. Carbon fiber is reserved for high-performance racing yachts due to its cost.

Keel Construction Methods

Keel construction varies based on the boat’s design and purpose. Traditional methods include:

- Frame-First Construction: The keel is laid first, followed by the stem, sternpost, and frames. The hull planks are then attached, as seen in carvel-built ships. A keelson may be bolted over the keel for added strength.

- Plank-First Construction: Common in clinker-built boats, where overlapping planks form the hull, with the keel providing the structural foundation.

- Encapsulated Keel Construction: The keel is molded as part of the hull, with lead ballast bonded inside, ensuring a seamless, robust structure.

- Bolted Keel Construction: A fin or bulb keel is bolted to the hull, allowing for easier repairs but requiring regular inspection of bolts for corrosion.

Modern shipbuilding often uses pre-fabricated hull sections, but the keel remains the starting point for sailboat construction, ensuring structural integrity.

Choosing the Right Keel for Your Sailing Needs

Selecting the appropriate keel depends on your sailing goals, cruising grounds, and boat type. Below are key considerations:

- Coastal Cruising: Fin keels or lifting keels (e.g., Rustler 33 or 57) offer maneuverability and shallow draft for harbors and anchorages. Wing keels are ideal for areas like the Bahamas.

- Offshore Cruising: Full keels or encapsulated keels (e.g., Rustler 36, 37, 42) provide stability and durability for long passages and rough seas.

- Racing: Bulb or wing keels maximize speed and upwind performance, suitable for competitive sailing.

- Tidal Areas: Twin keels or lifting keels allow grounding without compromising stability.

Draft vs. Stability Trade-Off

Deeper keels improve stability by lowering the center of gravity but restrict access to shallow waters. For example, the Rustler 44 uses a bulbed fin keel to maintain stability with a moderate draft (around 2.1 meters), while the Rustler 57’s lifting keel reduces draft to 2 meters when raised, expanding cruising options.

Ballast and Stability

The ballast ratio (ballast weight divided by total boat weight) is a key indicator of stability. Offshore sailboats typically have a ballast ratio of 35–40%, while coastal cruisers may range from 25–35%. Higher ratios indicate better righting ability but may increase draft or weight.

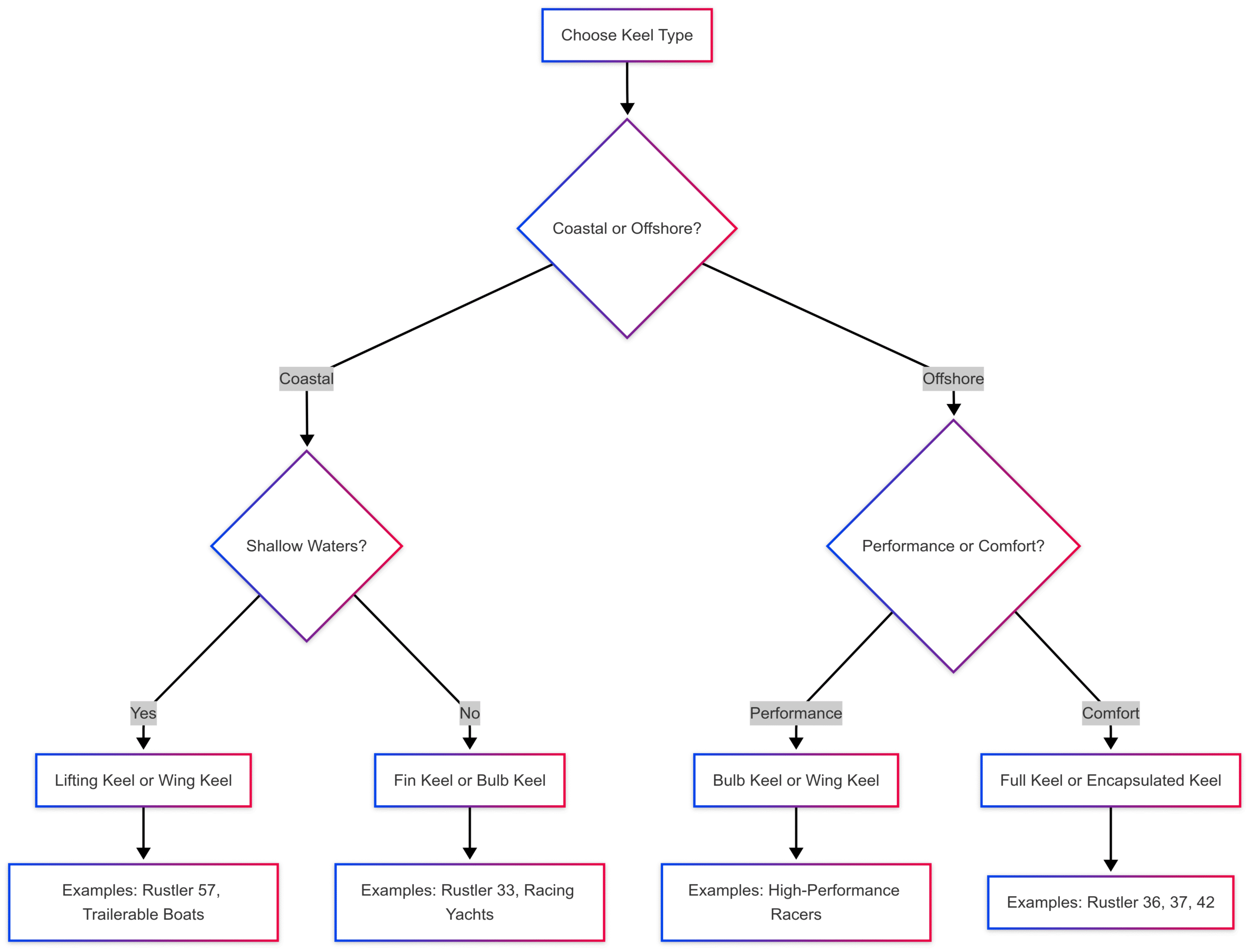

Chart: Keel Design Decision Tree

Below is a decision tree to guide keel selection based on sailing needs:

Keel Maintenance and Care

Keels are robust but require regular maintenance to ensure performance and safety:

- Inspection: Check for corrosion (especially on iron or steel keels), cracks, or loose bolts in bolted keels.

- Cleaning: Remove barnacles, algae, and debris using marine-grade cleaners to reduce drag.

- Coatings: Apply antifouling paint to prevent marine growth and protect metal keels from corrosion.

- Repairs: Address grounding damage promptly to prevent structural issues.

For cleaning, products like Captains Preferred boat brushes and marine cleaners are recommended for maintaining a keel’s hydrodynamic efficiency.

Keel Design Innovations

Modern keel designs continue to evolve, balancing performance, stability, and versatility:

- Canting Keels: Used in high-performance racing yachts, these keels pivot sideways to counter heeling, allowing a more upright sailing position.

- Carbon Fiber Keels: Lightweight and strong, these are increasingly used in racing boats to reduce weight without sacrificing strength.

- Hybrid Lifting Keels: Designs like the Rustler 57’s lifting keel combine a fixed lead stub with a retractable bronze fin, offering versatility without compromising interior space.

Pricing Considerations

Keel design impacts boat cost due to materials and construction complexity. Below are approximate price ranges for Rustler yachts with different keel types (based on typical market trends for high-quality cruising yachts):

| Model | Keel Type | Approx. Price (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Rustler 24 | Full Keel | $50,000–$80,000 |

| Rustler 33 | Fin Keel | $100,000–$150,000 |

| Rustler 36 | Full Keel (Encapsulated) | $150,000–$200,000 |

| Rustler 37 | Encapsulated Fin Keel | $200,000–$250,000 |

| Rustler 42 | Encapsulated Fin Keel | $300,000–$400,000 |

| Rustler 44 | Bulbed Fin Keel | $400,000–$500,000 |

| Rustler 57 | Lifting Keel (Optional) | $600,000–$800,000 |

Conclusion

The keel is a sailboat’s unsung hero, providing stability, directional control, and performance. From the robust full keels of offshore cruisers to the agile fin keels of coastal racers, each design serves a specific purpose. By understanding keel types, materials, and their applications, sailors can choose the best design for their cruising needs, whether navigating shallow harbors or crossing oceans. Regular maintenance and innovative designs, like lifting or canting keels, ensure that keels continue to evolve, enhancing safety and enjoyment on the water.

For further questions about keel designs or to explore Rustler yachts, contact the manufacturer or subscribe to their newsletter for the latest insights.

Happy Boating!

Share Keel construction and design explained with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Sailboat Keel Types: Illustrated Guide (Bilge, Fin, Full) until we meet in the next article.